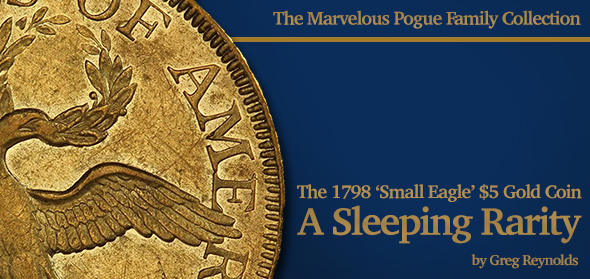

Coin Rarities & Related Topics: News and Analysis regarding scarce coins, coin markets, and the coin collecting community #293

A Weekly CoinWeek Column by Greg Reynolds….

On September 30, 2015, the Pogue II sale will be conducted by Stack’s-Bowers, “in association with Sotheby’s,” in New York.

The rarest coin in the sale is the 1798 ‘Small Eagle’ $5 gold coin (U.S. half eagle). The Pogue Collection piece is PCGS graded “AU-55.” According to Brent Pogue, it was “without question” previously graded AU-55 by NGC and is likely to be the coin that NGC currently reports as having been graded AU-55. The Pogue coin seems to be the finest of just six that survive.

The first auction of the Pogue Family Collection was held on May 19, and I covered 18th century rarities in depth. Later, 1820 quarters in that auction were the subject of an analysis. Some general information about the collection may be found in part 1 of this series. (Please click on words in blue to refer to related articles.)

Only one 1798 ‘Small Eagle’ $5 gold coin has been auctioned since the Eliasberg sale of October 1982. In 2000, the Goldbergs auctioned the Kardatzke coin. John Dannreuther reported that this piece surfaced in the South in 1996. Saul Teichman concluded, in a convincing fashion, that the Kardatzke coin is the Atwater piece that was sold by the firm of B. Max Mehl in a famous mail bid sale in 1946. It was earlier in the epic collection of George Earle.

These are sleeping rarities, as 1798 ‘Small Eagle’ half eagles very infrequently trade. They are very rarely even seen! Over the past thirty years, they have not often been topics of conversation.

Of all U.S. coin denominations, half eagles are the most challenging to seriously collect ‘by date,’ as there are so many Great Rarities in the series. Two of the six known 1798 ‘Small Eagle’ half eagles are in the Smithsonian, and the long-term status of the Eliasberg-Bass piece is unclear. It may not be in the ANA museum forever.

Introduction to Half Eagles

Half eagles (U.S. $5 gold coins) were minted from 1795 to 1929, though not during every year. Those with a ‘Small Eagle’ reverse date from 1795 to 1798. Bust Right, Heraldic Eagle coins, the second type, date from 1797 to 1807, plus some dated “1795.” It is widely believed that 1795 half eagles with the Heraldic Eagle reverse were minted later than 1796.

There are eight design types of U.S. half eagles: Bust Right – Small Eagle (1795-98), Bust Right – Heraldic Eagle (“1795”-1807), Bust Left (1807-12), Capped Head (1813-34), Classic Head (1834-38), Liberty Head ‘No Motto’ (1839-66), Liberty Head [with] ‘Motto’ (1866-1907), and Indian Head (1908-29). Some reference guides list two types of Capped Head Half Eagles, ‘Large’ (1813-29) and ‘Small’ (1829-24), though these are very similar.

The two meanings of the word ‘eagle’ in relation to U.S. gold coins can be confusing. The word ‘eagle’ refers to representations of the bird as coin design elements and to coin denominations. An eagle is $10 gold coin and a quarter eagle is a $2½ gold coin.

Since 1986, the U.S. Mint has, on many occasions, produced commemorative $5 gold pieces. These are not similar to any real coins and are a subject apart from the half eagles that were minted as a regular part of U.S. coinage from 1795 to 1929.

‘Bust Right’ half eagles depict a bust of Miss Liberty facing to the observer’s right on the obverse (front) of each coin. On the first type of half eagles, this Bust Right obverse design was paired with a ‘Small Eagle’ reverse design. The portrait of an eagle is not really small; it is just smaller than the portrait in the ‘Heraldic Eagle’ design, which is not all that large on $5 gold coins. The term ‘Heraldic Eagle’ is much more accurate than the term ‘Large Eagle,’ as this portrait of an eagle with a shield stems from the Great Seal of the United States and has particular meanings in the field of heraldry.

“Mint Director Elias Boudinot wished to use the Great Seal as was done in Europe at that time with their national emblems. It would have been cleared through President Washington, however,” reports R. W. Julian, in his response to my inquiry. Julian is the leading researcher of documents relating to the early years of the U.S. Mint.

This is not just a die variety. The 1798 ‘Small Eagle’ issue is especially distinctive as the ‘Heraldic Eagle’ reverse (tail) design replaced the ‘Small Eagle’ design in 1797. Most 1798 $5 gold coins have a ‘Heraldic Eagle’ reverse. The 1798 ‘Small Eagle’ is a curiosity in the sense that a reverse die from an earlier design type was employed to produce a small number of coins. A 1798 is needed for a complete set of Bust, ‘Small Eagle’ half eagles.

In 1798, Draped Bust silver dollars with a ‘Small Eagle’ reverse and those with a ‘Heraldic Eagle’ reverse were minted. There are no 1797 ‘Heraldic Eagle’ dollars, however, while there are 1797 ‘Heraldic Eagle’ $5 coins. The 1798 ‘Small Eagle’ $5 coins are, in some sense, ‘out of order.’

If silver dollars with a ‘Small Eagle’ reverse were produced earlier in 1798 than silver dollars with a ‘Heraldic Eagle’ reverse, it could be argued that 1798 silver dollars were made in order. In reality, though, U.S. Mint personnel were struggling to produce coins, with barely adequate knowledge and limited resources. At the time, the U.S. Mint was controversial and underfunded. Moreover, yellow fever epidemics in Philadelphia during the 1790s significantly affected productivity. It was not a priority to use reverse dies in some kind of ‘proper’ sequence.

In 1798, most U.S. Mint employees did not have the time or the energy to reflect often about the interests of coin collectors. They did not have vacuum cleaners, air conditioning or electric engines of any kind. U.S. Mint personnel tended to work nine or ten hours a day and they had to focus on pressing tasks.

Besides, the fact that there are so many varieties and anomalies relating to early U.S. coinage contributes to the appeal of the coins from this time period. Early U.S. coins are especially interesting. The noteworthy aspects of this issue have not received much attention since the 1950s, because the surviving pieces have been sleeping, ‘out of the limelight.’

Pedigree of The Pogue Coin

This coin was privately acquired by Brent’s father from Mike Brownlee in 1979. “It was Brownlee who encouraged us to collect early eagles and half eagles,” Brent Pogue recollects. He said that “half eagles were the hardest series to collect.” Brent and his dad were eager to take on a challenge. “My father loved the chase, beating out the competition for the best coins,” Brent notes. “My father and I fell in love with the artistry and size of early half eagles. We wanted to build the all-time finest collection of them,” says Pogue. They did so.

The Farouk-Pogue 1798 ‘Small Eagle’ $5 gold coin is also pedigreed to John Murrell, who was the “owner of the greatest unknown collection of U.S. gold coins ever assembled,” according to an article by Doug Winter in 2012. Murrell and Brownlee were both in the Dallas area.

Many years ago, Saul Teichman determined that the Pogue 1798 ‘Small Eagle’ five was earlier in the collections of Farouk and Baldenhofer. A few years ago, W. David Perkins revealed Baldenhofer’s true first name, William, and the origin of the fabricated ‘first name’ that appears in the auction catalogue in 1955, “Farish.”

The Stack’s sale of the “Farish Baldenhofer Collection” was conducted in November 1955. In an article of mine that was published on July 9, 2014, I noted that the Norweb 1797 half sold for $1750, an 1838-O half brought $3200, and an 1885 Trade Dollar realized $4000. I then pointed out that all of the five known 1885 Trade Dollars are each currently worth more than $1.25 million.

The Pogue 1798 ‘Small Eagle’ half eagle reportedly brought $6000 in 1955, much more than any of the other rarities in the Baldenhofer sale. The Norweb 1797 half, which realized $1750 in 1955, was auctioned for $1,380,000 in 2008 and for $1,292,500 in 2014. The Baldenhofer 1838-O half appeared in the Heritage FUN auction of January 2013, in which it garnered $734,375, more than 200 times the result in 1955. After Sept. 30, it will be interesting to reflect upon the relative price realized of the Farouk-Baldenhofer-Pogue 1798 in relation to the prices for other rarities in the Pogue I and II sales.

Extreme Rarity of This Coin

It is often stated that seven or eight exist. Saul Teichman hypothesizes that six are known and Saul has supplied his data to Ron Guth at PCGS CoinFacts and to John Kraljevich, who is the lead cataloguer of the Pogue coins. On this matter, Saul’s research and conclusions are certainly sound, though it is impossible to know for sure the number that exist. It is fair to assert that six are currently known and another has not been rumored by sources in the mainstream.

Two of the six are contained in the national numismatic collection of the Smithsonian Institution. While the Eliasberg coin is currently at the ANA museum, it remains part of the Harry Bass Collection and is thus not owned by the ANA. Many coins and other numismatic items in this collection have been consigned to public auction, including some recently. In August 2011, Stack’s-Bowers auctioned educational notes and various other paper money items from the Harry Bass Collection. In August 2014, Heritage auctioned more than twenty-five patterns, including some famous varieties, from the Harry Bass Collection. A majority of the patterns and U.S. gold coins in the Bass Collection were auctioned by Bowers & Merena in 1999 and 2000.

As so much of the Bass Collection has been consigned to auction, is it plausible that the Eliasberg-Bass 1798 ‘Small Eagle’ half eagle will be auctioned as well? Was it accurate for the Pogue II catalogue to refer to the Eliasberg-Bass piece as being ‘impounded”?

Regarding the four outside of the Smithsonian, only one has surfaced since 1983, as far as I know. The Earle-Atwater coin was twice offered by the Goldbergs, on June 1, 1999 and on June 6, 2000. “In 2000 the consignor was Dr. Jon Kardatzke and the coin was sold,” Ira Goldberg now reports. There are no longer images of the Kardatzke coin on the Goldbergs web site. It was PCGS graded Extremely Fine-40 well before June 1999. Dr. Kardatzke is a retired physician and the founder of the Museum of World Treasures in Wichita, Kansas, which houses many items that he personally collected. Jay Parrino or his agent may have been the successful bidder in 2000; Parrino did own this coin at some point.

Regarding the four outside of the Smithsonian, only one has surfaced since 1983, as far as I know. The Earle-Atwater coin was twice offered by the Goldbergs, on June 1, 1999 and on June 6, 2000. “In 2000 the consignor was Dr. Jon Kardatzke and the coin was sold,” Ira Goldberg now reports. There are no longer images of the Kardatzke coin on the Goldbergs web site. It was PCGS graded Extremely Fine-40 well before June 1999. Dr. Kardatzke is a retired physician and the founder of the Museum of World Treasures in Wichita, Kansas, which houses many items that he personally collected. Jay Parrino or his agent may have been the successful bidder in 2000; Parrino did own this coin at some point.

The Garrett piece was catalogued as grading “Extremely Fine-40” and was auctioned by Bowers & Ruddy on November 29, 1979, at the St. Moritz hotel in New York. The Eliasberg auctions of 1982, 1996 and 1997 were held at the same location. The price realized in 1979 was $110,000.

It seems likely that the Garrett Family coin was later handled by Jeff Garrett, after it was offered in the Auction ’83 event. Jeff is not related to the family that formed the epic Garrett Collection. Jeff Garrett is currently president of the ANA.

Jeff “purchased the 1798 Small Eagle $5 from Kevin Lipton sometime in the 1980s.” Jeff then advertised this coin. “A gentleman called one day asking the best price. He flew to Lexington, picked up the coin and was never seen again. He declined to give his name,” Jeff says. The buyer did not pay with a check.

The Garrett coin could be the coin that the NGC has graded EF-45. It is also possible that the PCGS graded EF-40, Earle-Atwater-Kardatzke coin may have been NGC graded as EF-45 at some point.

It is probable that the Eliasberg-Bass coin was never submitted to PCGS or NGC. Harry Bass acquired the coin at the Eliasberg sale of U.S. gold coins in October 1982 or soon afterwards. Bass did not wish for any of his coins to be certified. Generally, Bass was an opponent of third party grading and encapsulation.

Published images suggest that the Farouk-Baldenhofer-Pogue coin has much more detail than the Garrett, Earle-Atwater-Kardatzke and Eliasberg-Bass coins. John Dannreuther suggests that the two in the Smithsonian have serious problems. No one is expecting the finest 1798 half eagles to be of the same quality as the finest 1898 half eagles. Imperfections are parts of the personalities of the coins.

Missing from Many Epic Collections

While 1798 ‘Small Eagle’ $5 gold coins were sleeping, they were missing from many major collections that contained a large number of truly rare U.S. gold coins. The acquisition of the Parmelee coin in 1890 by the U.S. Mint and the donation of the Lilly coin to the Smithsonian in the 1960s resulted in two being unavailable to collectors. As far as I know, these were never really emphasized at the Smithsonian. Visitors have been far more likely to see and talk about 1804 silver dollars, a 1913 Liberty nickel, Proof 1821 coins, the 1849 double eagle, 1933 double eagles, $50 gold patterns, or 1822 half eagles.

Apparently, a 1798 ‘Small Eagle’ half eagle was not in the Norweb Family or James A. Stack, Sr. (JAS) collections, each of which included many gold rarities. The Norweb U.S. coins were auctioned by Bowers & Merena in 1987 and 1988. The primary sale of gold rarities from the JAS collection was by Stack’s (NY) in October 1994, though some may have been auctioned in March 1995.

There was not one in the Richmond or Bently collections either, and these are perhaps the most extensive assemblages of U.S. gold coins to be auctioned since the Bass sales of 1999 and 2000. The gold coins in the Richmond Collection were auctioned by DLRC in 2004 and the Bently Collection was sold by Heritage in 2014.

The fact that 1798 ‘Small Eagle’ $5 coins were missing from epic collections, where they would seem to fit well, is a reason why this Great Rarity has been dormant. Many people have forgotten about it. In advance of the upcoming Pogue II event, there has been much more discussion of the Oswald-Hayes 1794 silver dollar, multiple gem quality 1795 silver dollars, an 1817/4 half dollar, and the Garrett 1795 $10 gold coin, although the 1798 ‘Small Eagle’ $5 coin is rarer than any of these.

During the era from around 1890 to the 1950s, this was a coin issue that was discussed fairly often among coin enthusiasts. In the past, a 1798 ‘Small Eagle’ half eagle was worth as much or more as almost all other Great Rarities.

When the collection of George Earle was catalogued for auction in June 1912, Henry Chapman declared that the Earle-Atwater-Kardatzke 1798 ‘Small Eagle’ five is the “rarest U. S. gold coin of the regular series,” and Chapman “confidently and hopefully” suggested that “it will command a price exceeding any heretofore obtained for a United States gold coin.” A record was set. Henry Chapman himself “purchased” the Earle 1798 ‘Small Eagle’ $5 gold coin for “$3000.”

When the collection of George Earle was catalogued for auction in June 1912, Henry Chapman declared that the Earle-Atwater-Kardatzke 1798 ‘Small Eagle’ five is the “rarest U. S. gold coin of the regular series,” and Chapman “confidently and hopefully” suggested that “it will command a price exceeding any heretofore obtained for a United States gold coin.” A record was set. Henry Chapman himself “purchased” the Earle 1798 ‘Small Eagle’ $5 gold coin for “$3000.”

In the same Earle sale, a 1796 ‘No Stars’ quarter eagle realized $90, a 1796 ‘with stars’ sold for $215, and a 1797 brought $140. There is a good chance that the Earle 1797 quarter eagle is or was of equal or higher quality than the Pogue 1797 quarter eagle that brought $152,750 on May 19, 2015, more than a thousand times as much as the Earle 1797 quarter eagle realized in 1912. The Farouk-Baldenhofer-Pogue 1798 ‘Small Eagle’ five is superior to the Earle-Atwater-Kardatzke coin.

The Murdoch-Earle 1794 silver dollar sold for $620 in June 1912. Over the past century, the Murdoch-Earle 1794 was in the Atwater, Cass and Bass collections. In April 2009, Heritage auctioned it for $503,125, more than 800 times as much. It was then NGC graded MS-61. Earlier, in June 2005, Heritage auctioned this same Murdoch-Earle-Atwater-Bass 1794 dollar for $747,500, more than 1200 times the auction result in 1912.

So, $620 was paid in 1912 for a 1794 silver dollar, which was later NGC graded MS-61, and $3000 was paid for a 1798 ‘Small Eagle’ $5 gold piece, which was later PCGS graded EF-40. These facts are not the only evidence that 1798 ‘Small Eagle’ half eagles were generally worth far more than 1794 silver dollars during the early part of the 20th century. Prices for 1798 ‘Small Eagle’ fives in other sales substantiate this point.

From 1890 to the 1930s, five of the six were ‘in play,’ sometimes more than once, and were probably discussed at length in private conversations even by people who did see any of them. Although I have been covering rare coin auctions for more than twenty years, the Pogue 1798 ‘Small Eagle’ five was the first that I have ever held. There was not one in the Christie’s/Spink sale of coins from the Byron Reed Collection in 1996, which featured many very rare half eagles. There was never one in a Heritage Platinum Night or Stack’s-Bowers Rarities Night event.

Afterthoughts

While it may be overwhelming to contemplate a set of all pre-1840 half eagles, a set of ‘Small Eagle’ issues ‘by date’ would be practical if the Farouk-Baldenhofer-Pogue 1798 ‘Small Eagle’ is acquired. Finding representatives of the other dates would not be particularly difficult.

Hundreds of 1795 ‘Small Eagle’ fives are around. These are neat type coins, as U.S. gold coins were first struck in 1795.

There are no 1796 half eagles with normal numerals. Although the 1796/5 is very rare, at least five were sold in 2014 and at least one is available every year.

There are two major varieties of 1797 ‘Small Eagle’ $5 coins, the first has fifteen stars on the obverse and the second has sixteen stars. It is best to acquire one or the other before deciding whether it is really necessary to own one of each. For collectors of U.S. coins who are focused upon rarity and historical importance, prevailing market levels for Bust Right half eagles may be particularly appealing.

©2015 Greg Reynolds