By David Provost for CoinWeek …..

Author’s Note: My intention for this series of “stories” is to present lesser-known information about the US commemorative coins series derived from my original research in the records of Congress and/or the reports and correspondence of the individual coin sponsors. The information presented will not simply be a reworking of the information presented in the standard reference works on the series. I sincerely hope you enjoy the backstories presented in this series and I welcome your comments and suggestions.

Author’s Note: My intention for this series of “stories” is to present lesser-known information about the US commemorative coins series derived from my original research in the records of Congress and/or the reports and correspondence of the individual coin sponsors. The information presented will not simply be a reworking of the information presented in the standard reference works on the series. I sincerely hope you enjoy the backstories presented in this series and I welcome your comments and suggestions.

* * *

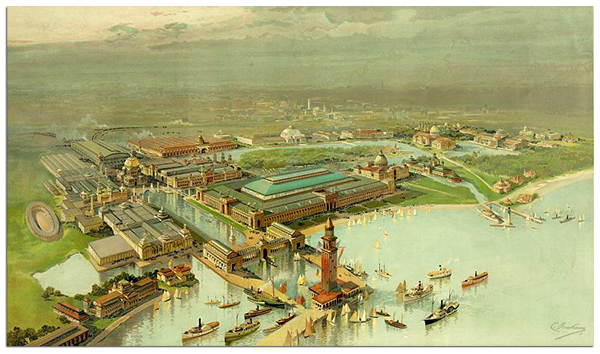

World’s Columbian Exposition

The first Congressionally-authorized US commemorative coin was not part of the original vision for the US Government’s involvement in the world’s fair that would come to be known as the “World’s Columbian Exposition.” In fact, it can be said that the Columbian half dollar only came about because of incomplete and inaccurate financial projections for building, promoting, and staging the Exposition.

To fully understand how the Columbian half dollar came about, it’s necessary to review how the Exposition was financed.

As the 400th anniversary of Christopher Columbus’ landing in the New World approached, thoughts of holding a grand exposition in its honor formed across the country with a number of US cities competing to host the event. Chicago, New York, St. Louis, and Washington, DC were serious candidates to host the fair, with each submitting a “host city” proposal to Congress.

Chicago pursued the exposition aggressively from the start. In July 1889, the Chicago City Council passed a resolution instructing the mayor to appoint a committee of 100 members to serve the interests of the city regarding the fair and to lobby the US Congress on its behalf. In August 1889, “The World’s Exposition of 1892” company was incorporated under the laws of the State of Illinois; it raised $5 million from its initial stock offering.

Over the summer of 1890, Congress debated the merits of the proposals received and ultimately selected Chicago as the site for the Exposition. The US Government formally committed to participate in the Exposition with the passage and approval of the Act of April 25, 1890. The Act provided “for celebrating the four hundredth anniversary of the discovery of America by Christopher Columbus, by holding an international exposition of arts, industries, manufactures, and products of the soil, mine, and sea, in the city of Chicago, in the State of Illinois.”

The Act created the World’s Columbian Commission (WCC) which was to lead the development of the plan and determination of the scope for the Exposition. The Commission was to be made up of two commissioners from each state and territory plus Washington, DC, and include eight “at large” commissioners. The Illinois-based Exposition corporation was tasked with providing the site to be used for the Exposition and for the construction of the necessary administrative buildings and exhibition halls on the site.

The Act also included a $320,000 appropriation to be used to cover the expenses of the WCC, prepare and transport the exhibits to be displayed by the US Government, and construct a suitable building to house the exhibits; it also covered miscellaneous anticipated expenses related to admission of foreign goods to the Exposition. A second Act was approved in March 1891 which provided an additional $765,500 to be used for the same purposes outlined in the first Act.

The Exposition company secured a 633-acre site in Jackson Park on the shore of Lake Michigan from the City of Chicago. The organizers began construction of the fairgrounds using the initial money raised from its stock sale. It was at this point that a clearer picture of the true costs of holding the Exposition began to emerge.

This figure was soon revised upward again after reviews by the House Committee on Appropriations and the House Select Committee on the Columbian Exposition. The new figure was pegged at a minimum of $17,000,000. This figure included estimates for domestic and international promotional costs, something that previous estimates did not fully consider.

Based on this new financial reality, the World’s Columbian Exposition and the World’s Columbian Commission launched a fund-raising initiative that brought in nearly $4,000,000 of appropriations from US states and territories, along with almost $5,000,000 from foreign governments.

Even with this, however, the Exposition estimated that without a further appropriation of $5,000,000 by the US Congress, they would not be able to deliver an exposition that met the requirements of the plan prepared by the Government-appointed World’s Columbian Commission. Their only recourse, they believed, would be to stage an exposition that was smaller in scope.

The House Select Committee on the Columbian Exposition reported favorably on bill HR 9267 to the Committee of the Whole House indicating its support of a $5,000,000 appropriation to the World’s Columbian Exposition. The bill specified that the appropriation was to be provided via the minting of up to 10 million “Columbian half dollar” coins from uncurrent subsidiary silver coins currently held by the Treasury. The bill also specified that the $5,000,000 was to be repaid to the US Treasury upon the Exposition’s closing.

The House Select Committee on the Columbian Exposition reported favorably on bill HR 9267 to the Committee of the Whole House indicating its support of a $5,000,000 appropriation to the World’s Columbian Exposition. The bill specified that the appropriation was to be provided via the minting of up to 10 million “Columbian half dollar” coins from uncurrent subsidiary silver coins currently held by the Treasury. The bill also specified that the $5,000,000 was to be repaid to the US Treasury upon the Exposition’s closing.

Once reported out of Committee, the bill was strenuously debated in the House and Senate by supporters and detractors lined up on both sides of the aisle. The lengthy discussions produced multiple amendments to and substitutions for the original bill; it was ultimately passed but in an amended form. Among the key amendments were: 1) a reduction in the total appropriation from 10 million half dollar coins to five million; 2) a removal of the repayment provisions, the coins became an outright appropriation, and 3) the addition of a proviso requiring the Exposition to be closed on Sundays.

When President Benjamin Harrison signed the bill, the Act of August 5, 1892, officially authorized the first US commemorative coin. A case has been made by some researchers to acknowledge the 1848 gold quarter eagle with the “CAL” counterstamp as the first US commemorative coin. The counterstamp was meant to indicate that the coins were the first coins to be struck by the US Mint from California gold. The added mark was made at the request of Secretary of War W. L. Marcy at the time the gold ore was deposited at the Mint. No permission or authorization for the modification to the design of the quarter eagle was sought from Congress, however. I agree that these quarter eagles have a commemorative nature, but I do not consider them as part of the “official” US commemorative coin series. I consider only Congressionally-authorized coins to be included.

The enabling legislation for the Columbian half-dollars did not limit production to a single Mint facility. Had mintmark collecting been more popular at the time, we might today be collecting these coins in three-piece sets with an example each from Philadelphia, New Orleans, and San Francisco. Instead, all five million coins authorized were struck at the US Mint in Philadelphia. The coins were struck for the Exposition in 1892 and 1893, with 950,000 coins struck in the former year and 4,050,000 (plus assay coins) struck in 1893; the coins are dated with the year of their striking.

The souvenir coins were sold for $1.00 each at the Exposition but actual sales fell far short of expectations. An 1894 audit of the Exposition’s finances lists receipts from the “Premium on souvenir coins” as $517,556.43. Understanding that this figure includes approximately $18,000 worth of premiums from sales of the 1893 Isabella quarter-dollar; the net premium value achieved for sales of the 1892-93 Columbian half dollar is approximately $500,000. Considering the standard premium on each coin was $0.50 (Selling Price – Face Value), this suggests total sales of the Columbian coin of approximately 1,000,000 coins. Approximately 1,500,000 additional coins were released into circulation after the Exposition closed.

The souvenir coins were sold for $1.00 each at the Exposition but actual sales fell far short of expectations. An 1894 audit of the Exposition’s finances lists receipts from the “Premium on souvenir coins” as $517,556.43. Understanding that this figure includes approximately $18,000 worth of premiums from sales of the 1893 Isabella quarter-dollar; the net premium value achieved for sales of the 1892-93 Columbian half dollar is approximately $500,000. Considering the standard premium on each coin was $0.50 (Selling Price – Face Value), this suggests total sales of the Columbian coin of approximately 1,000,000 coins. Approximately 1,500,000 additional coins were released into circulation after the Exposition closed.

In addition to individual coin sales to fairgoers, the Exposition also made bulk sales to companies wishing to use the coins for promotional purchases. One such bulk purchaser was Wells, Fargo & Company who turned their purchase into one of the Exposition’s more interesting pieces of coin-related collectible ephemera.

The famed company was organized in 1852 by Henry Wells, William G. Fargo, and others in response to the immense profit potential of the burgeoning California mineral industry. The company was capitalized with a $300,000 investment from its organizers and was initially structured to offer banking and express shipping services in California. It quickly established offices in all of the state’s mining camps of significance and became the dominant provider of its services.

From these roots, the company continued to grow and expand its geographic reach. By the time of the Columbian Exposition in 1893, it had grown to include 2,829 offices located across the United States along with agents in England, France, Germany, Italy, Belgium, Denmark, Norway, and Panama. Over 6,000 employees enabled the company to conduct its business over 36,000 miles of railroads, stagecoach roads, and water routes. Wells Fargo handled a significant amount of transport of goods to and from the Exposition.

Ever aware of its history and role in supporting the development of the American West, Wells Fargo launched its first-ever historical exhibit at the World’s Columbian Exposition; it was located in the California Building. The exhibit featured a collection of more than 200 historical artifacts. Featured were photographs of company employees and offices, signs, and posters used to promote its business, and various noteworthy pieces of company correspondence. Also featured were “Cut-off” shotguns used by company employees to defend their shipments and a shotgun used by the infamous outlaw “Black Bart” (real name: Charles E. Boles) who robbed Wells Fargo stagecoaches 28 different times!

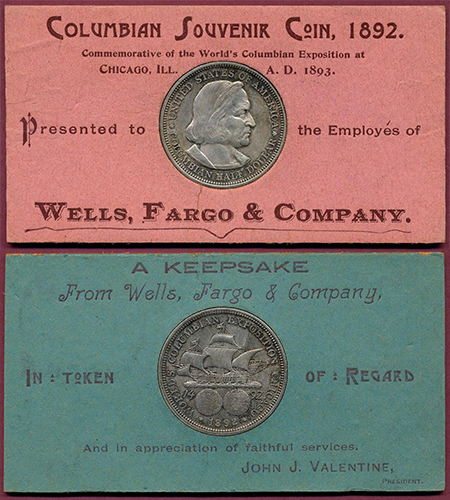

For numismatists, of note is exhibit item number 167. It is listed as “A Keepsake” and is described as an 1892 “Columbian Souvenir Coin” presented along with its display card and a copy of the letter President John J. Valentine sent to employees regarding the coin.

In his January 2, 1893 letter, Valentine announced that the company had purchased a quantity of the Columbian half dollars and would be presenting each employee with a “Souvenir Coin” as an “aid in perpetuating a pleasant recollection of the great commemorative event of the present year, to wit, the World’s Columbian Exposition at Chicago, Illinois, and to secure at the same time a little remembrance of our friendly interest in you individually, in appreciation of your faithful services.”

Valentine continued, “The coins are designed simply as souvenirs or keepsakes, and as such will, it is thought, enhance in value from year to year. It is in this spirit our presentation is made, with the hope that as a token of our regard they will be prized and preserved.”

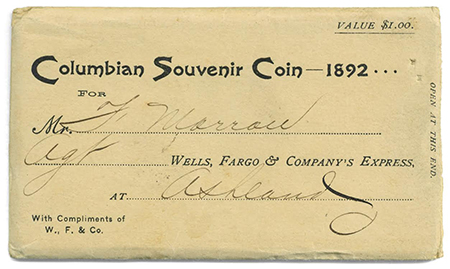

To receive a coin, employees applied to either their Superintendent or Route Agent; Office Agents and their reports were to request coins via their Superintendent, Messengers were to apply through their Route Agent.

The coins were distributed in custom-printed cardboard holders that allowed both sides of the coin to be seen. The front of the card was pink in color and featured descriptive text regarding the coin’s commemorative nature and noted its intent as a presentation piece. The back of the card was green and featured a message from John J. Valentine: “A Keepsake from Wells, Fargo & Company. / In Token of Regard / And in appreciation of faithful services.“

The holder was inserted in a pre-printed envelope which left space for the recipient’s name and title to be added, along with their home-office location. The envelope also made note of the coin’s value at $1.00 to further support the piece’s value over its face denomination.

The coin and presentation card was not available for sale to the general public. The Wells Fargo archives indicate that 1,666 of the coins in the presentation holders were distributed to employees, with 124 applied for coins left undistributed for unidentified reasons. Clearly, not all of the company’s 6,000 employees applied for one of the coins when they had the chance.

In 1909, an internal memo notes that 600 coins still on hand were sold to multiple parties in group lots at just a cent or two over face value. This suggests that the company likely purchased approximately 2,500 of the coins at the time of the Exposition.

Unlike many of the commemorative coins that would follow it, especially those from the 1930s, the Columbian half dollars were not sold by their sponsor in any type of special packaging. For collectors seeking such pieces of commemorative ephemera to enhance their collections, holders such as this piece from Wells Fargo are the next best thing to an “official” holder from the sponsor.

* * *

Have a comment, question or suggestion? Please contact me at [email protected].

Acknowledgement: I’d like to thank the staff at Wells Fargo Historical Services for their assistance regarding John J. Valentine’s “Souvenir Coin” letter and information regarding their coin’s distribution.

© Copyright D. Provost 2022. All rights reserved. Used with permission.

How many coins complete with the Wells Fargo holder do you estimate still exist, and what would be a fair retail price one could expect to pay for one?

J Griffin:

I would conservatively estimate that there are less than 100 of the coin holders still extant; they do not appear with any regularity at auction or via dealer stock. The Wells Fargo historical archive has several examples.

Market values for the piece vary based on the condition of the holder and coin, individually and together. Holders in nice condition with undamaged coins will typically sell for $500 (low end) to more than $1,000. (How much more will vary by dealer!)

Nice article, well written and informative.

I have one counter stamped with M3075. Do you know why it was stamped and what it means?

Thanks

I have two in great shape they were in circulation. Great article thanks ror the info

JonGrillo