By Charles Morgan and Hubert Walker for CoinWeek ….

Don’t worry. This isn’t an essay on literary theory, or some nostalgic lament. Instead, we’d like to take a moment to explain something critical to our understanding of the stylistic and political implications behind what’s known as the Modern Era of U.S. coinage, and how that era has already passed, having been replaced by a new era of postmodernism.

It‘s hard to overstate the importance of this. The passing of Modernism has repercussions far beyond the physical designs and denominations of the coins themselves. It also speaks to our expectations of money and the way it’s used. Just as Theodore Roosevelt’s “Pet Crime” represented a sea change in the way our nation projected power and prestige through the sculptural beauty of its gold and silver coins, the Postmodern Era reflects a dramatic reversal of the way the Mint and its overseers view coin collectors and the utility of America’s original currency.

To put things into perspective, we proffer that the 20th century saw three distinct periods: The Golden Age (1907-1933), The Modern Age (1932-1982), and the Postmodern (1982-present).

THE GOLDEN AGE

Coin art, like art rendered on larger canvases, is a reflection of the culture that made it. Artists are of their time, and we must take into account how they understand themselves and their work. Augustus Saint-Gaudens and his acolytes were attempting to elevate our national coinage by coupling allegorical symbolism with high-relief coin sculpture borrowed from antiquity. The goal was to increase the global stature of America’s economy by refining the aesthetics of the economic engine’s primary lubricant: money itself.

The Golden Age of United States coinage was heavily steeped in European styles of the turn of the century. American coins combined the Beaux-Arts academic approach with the design sensibilities of the Arts & Crafts movement, the dynamicism of Art Nouveau, and the spatial sense of Art Deco. The period also appropriated the classical past in an effort to appear timeless. When one looks at the Panama-Pacific International Exposition commemorative series, for example, one cannot help but see these influences. The half dollar portrays a sensuous depiction of the American “goddess” Columbia on the obverse, taken from Oscar Roty’s portrait of the Sower on the French Franc. The design of the golden dollar depicts Labor in terms akin to socialist handbills. The quarter eagle features Columbia again, this time astride the mythical hippocampus. And the $50 gold pieces are impressive works of numismatic innovation using classical, pan-Mediterranean motifs.

The Golden Age of United States coinage was heavily steeped in European styles of the turn of the century. American coins combined the Beaux-Arts academic approach with the design sensibilities of the Arts & Crafts movement, the dynamicism of Art Nouveau, and the spatial sense of Art Deco. The period also appropriated the classical past in an effort to appear timeless. When one looks at the Panama-Pacific International Exposition commemorative series, for example, one cannot help but see these influences. The half dollar portrays a sensuous depiction of the American “goddess” Columbia on the obverse, taken from Oscar Roty’s portrait of the Sower on the French Franc. The design of the golden dollar depicts Labor in terms akin to socialist handbills. The quarter eagle features Columbia again, this time astride the mythical hippocampus. And the $50 gold pieces are impressive works of numismatic innovation using classical, pan-Mediterranean motifs.

But more than that, the merger of such styles and design elements tied the relatively short scrawl of American history to the broad sweep of Western Civilization. It served as propaganda, to put Europe (and the rest of the world via Europe) on notice that America had arrived, that we were the legitimate heirs of a great cultural heritage and that our reign would be a worthy one. We don’t know if it was particularly effective on that count, but these coins – and coins like Saint-Gaudens’ eagle and double eagle* – certainly added to an American public’s already healthy sense of self-worth and vitality.

Of course, our circulating coinage was less flamboyant. This was the era of the Peace dollar and Buffalo nickel, among others. They were designed for use in the rough and supposedly unsentimental world of commerce, not as pieces de plaisir for the well-heeled hobbyist. But they did share the Panama-Pacific commemorative’s boldness, beauty, and cultivation of an American mythos.

The Golden Age lasted from approximately 1907 to 1933. That is when President Franklin Roosevelt issued Executive Order 6102, requiring gold coin, gold bullion, and gold certificates to be delivered to the government, literally ending the “Golden” Age of American coinage. It was succeeded by the longest-running epoch of American numismatics, the period commonly referred to as the Modern Era.

* Indeed, the years of mintage for Saint-Gaudens’ eagle and double eagle ARE the Golden Age. For further reading on the subject, we recommend Michael Moran’s Striking Change (Whitman, 2008).

ENTER THE MODERN ERA

Modernism in art, architecture, and even coins can be traced back academically to before the founding of the United States, but what we think of as “modern” in American coinage begins in 1932, with the introduction of the Washington quarter. It then continued to pick up steam as each denomination was redesigned, one by one, replacing the symbolic with paternalistic effigies of the Founding Fathers and the apotheosis of recently deceased presidents.

And while it’s possible to criticize this period as one of aesthetic stagnation, as a condemnation of the era this argument misses the point. While Golden Age coinage can be marked by its beautiful female forms and the way it borrowed European themes, the Modern Era reveals a confident and self-regarding America unafraid to project its political identity onto the international stage. The peoples of the world may be unfamiliar with the profiles of the various monarchs (save perhaps Queen Elizabeth II and a few others), but they all know George Washington, Abraham Lincoln, Thomas Jefferson, FDR and JFK when they see them on American coins and currency.

And while it’s possible to criticize this period as one of aesthetic stagnation, as a condemnation of the era this argument misses the point. While Golden Age coinage can be marked by its beautiful female forms and the way it borrowed European themes, the Modern Era reveals a confident and self-regarding America unafraid to project its political identity onto the international stage. The peoples of the world may be unfamiliar with the profiles of the various monarchs (save perhaps Queen Elizabeth II and a few others), but they all know George Washington, Abraham Lincoln, Thomas Jefferson, FDR and JFK when they see them on American coins and currency.

As the United States became the dominant hegemon militarily and economically, exporting trade goods and influence, it was on the back of our coinage and currency that we exported the brand of American democracy by portraying the best of our democratically-elected leaders. People may gripe about the disappearance of Lady Liberty when the Presidents took over, but one cannot deny the role of these men in shaping the world. At its best, the Modern Era will be remembered for its unity of design (always representative of a unity of purpose) and the confidence we had in our ideals.

A second aspect of the times, crucial to understanding the Modern Era, was the newfound utility of coins as a circulating medium. This was due to advances in vending technology and the implementation of sales tax, which made coins even more necessary for change. The automated exchange of legal tender in commerce is a concept that the founders of the Mint could never have dreamed of. America’s economy surged in the aftermath of World War II, and with so many Americans working at ever-increasing wages, the volume of coins and currency needed to facilitate commerce was immense. Technology, natural resources, and legislation strained to keep up. It is because of this that the debasement of coinage was inevitable.

And lastly, the Modern Era brought us what is arguably the full development of a thriving coin hobby. Millions of Americans began putting aside coins, perhaps in reaction to fears of losing money deposited in banks (as was the case for many during the Great Depression), or perhaps as an investment (books were written predicting enormous returns to those who squirreled away uncirculated rolls of coins).

American soldiers went off to war and returned with the exotic coins of far-away lands, these their fathers inspiring many of today’s collectors to start collecting in the first place. It was also a time when strange and rare creatures from the Golden Age could still be fished from the deeps of one’s pockets, even if only once in a blue moon. Besides, it was just a fun, wholesome and patriotic hobby that anyone could enjoy, practically the leisure embodiment of the American way of life.

Regular columns on coins appeared in newspapers and periodicals, from local markets to the national scene. Coin magazines, such as Chet Krause’s Numismatic News, began publication. Coin clubs and coin shows, which had operated since the 19th century, really exploded onto the scene in the fifties and sixties. This was also when many of the giants in the field either published their great works (Sheldon, Yeoman, etc.), or got their starts (Breen, et al.).

In addition, the high visibility of the hobby brought other players into the collectibles game. The Franklin Mint, founded in 1964 by serial entrepreneur Joseph Segel, got off to an especially auspicious start when it recruited former Chief Engraver Gilroy Roberts to work for them.

It was a time of high confidence in America and her symbols, the national economy, and our money.

THE COINS OF THE MODERN ERA

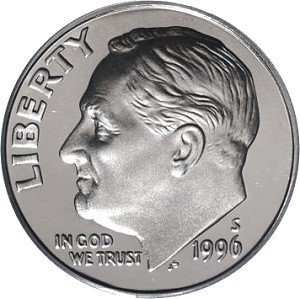

John Flanagan, a former assistant to Saint-Gaudens, married his interpretation of Jean-Antoine Houdon’s sculptural bust of Washington to the curvilinear form of a statuesque eagle surrounded by inscriptions in an Art Deco font. German-born immigrant Felix Schlag also borrowed from Houdon, and coupled his Jefferson with an at-the-time controversial head-on perspective of Monticello.[1] Frank Gasparro used this same perspective for the updated Lincoln cent reverse of 1959-2008. John Sinnock’s Roosevelt dime, perhaps the Modern Era’s most well-balanced coin, features a perfectly proportioned bust of Franklin Roosevelt on the obverse with LIBERTY offset to the left, giving the maximum amount of space to the main device. The reverse is a workshop in coin-art technique, with inscriptions encircling the torch of liberty, surrounded on each side by oak and olive branches, symbolizing that liberty is a balance of strength through war and the reasoned intelligence of peace.

The Franklin half dollar, more popular now and known for the elusiveness of certain issues with firm strikes and abrasion-free surfaces, is a spartan exercise in clean design. Its reverse was derivative of John Frederick Lewis’ design used on the 1926 Sesquicentennial commemorative half dollar, but approached from a modern perspective. Rescaled and absent the circular borders of the former, it was drawn from a lower perspective, which transformed the device into something symbolic and not merely transcribed.

The Franklin half dollar, more popular now and known for the elusiveness of certain issues with firm strikes and abrasion-free surfaces, is a spartan exercise in clean design. Its reverse was derivative of John Frederick Lewis’ design used on the 1926 Sesquicentennial commemorative half dollar, but approached from a modern perspective. Rescaled and absent the circular borders of the former, it was drawn from a lower perspective, which transformed the device into something symbolic and not merely transcribed.

This period of design change, starting in 1932 and lasting until 1963, can be considered the first half of the Modern Era. The second half, starting with the hasty memorialization of the slain John F. Kennedy and lasting through the beginning of the Reagan Administration, marks the end of the Modern Era proper.

SILVER VERSUS CLAD: THE MODERN ERA CONTINUES

Frequent pronouncements concerning the depletion of America’s silver stockpiles naturally led to hoarding and speculation. Nevertheless, the primary factor in the removal of silver from our nation’s coinage was the changing role coins played in the economy. The unprecedented demand for coins in the marketplace was driven by three factors: the increased discretionary income of Americans; inflationary pressures driving down the value of denominational coins, coupled with the rising value of bullion; and the proliferation of vending machines.

When the first cupronickel (Cu-Ni) clad coins were released into circulation in October-November 1965, Congressional leaders and President Johnson sought to instill confidence in the nation’s money by suggesting that the old coinage would circulate alongside the new for years. At first, clad barely made a dent. By 1967, however, clad coins started to gain a significant foothold while silver bled out of the economy. By 1970, one was lucky to find a silver coin in a roll of change. By 1971, nearly every silver coin had been removed from circulation.[2]

Of course, some silver coinage was still being produced. The Kennedy half dollar of 1965-1970 was fashioned from a silver-clad composition. But these coins rarely circulated. When the Eisenhower dollar was introduced in 1971, silver-clad “collector’s versions” were issued. In 1975-1976 silver-clad quarters, halves, and dollars were produced to coincide with the Bicentennial celebration. These items were meant to hearken back to the “Silver Era“, but they were mere gimmicks designed to sock it to collectors.

Of course, some silver coinage was still being produced. The Kennedy half dollar of 1965-1970 was fashioned from a silver-clad composition. But these coins rarely circulated. When the Eisenhower dollar was introduced in 1971, silver-clad “collector’s versions” were issued. In 1975-1976 silver-clad quarters, halves, and dollars were produced to coincide with the Bicentennial celebration. These items were meant to hearken back to the “Silver Era“, but they were mere gimmicks designed to sock it to collectors.

For some numismatists and coin collectors, the “Clad Era” is the dividing line between collectible and non-collectible. Superficially, the mintages of the Clad Era would be enough to scare off a collector more accustomed to buying coins with mintages around a couple million or less. But what gets overlooked is the paucity of well-struck and well-preserved coins from this time period. For many dates, from 1965 to sometime in the ‘80s, the presses were operating so feverishly that the coins being struck weren’t given enough time or pressure to fully come up. Other times, the dies and hubs were made of such poor quality that none of the coins they struck would be desirable to most collectors.

The Clad Era is certainly different in many fundamental and important ways from the pre-1964 silver period, but from a design and aesthetic perspective, it is a continuation of Modernism. It’s also a period of great success. While the quality of coins suffered during this period, the public acceptance of the new metals was quick and relatively painless. For younger generations of Americans, the date 1965 on a quarter has no particular significance. A quarter is a quarter.

SUSAN B. ANTHONY AND THE END OF MODERNISM

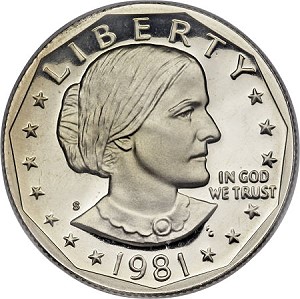

That the modern period ended in such a self-conscious manner, with the failed re-introduction of the “silver” dollar and the incongruous and bizarre coupling of early 20th century suffragette Susan B. Anthony with the twice-recycled Apollo 11 mission patch, speaks as much to the great sense of self-consciousness the country felt heading into the final two decades of the twentieth century as it does to any weakness in the design aesthetic that characterized modern coinage.

If anything, the Susan B. Anthony dollar rests between two worlds. It’s modern in the sense that it was an extension of the modern agenda: It was the intended successor of the one dollar Federal Reserve note and was seen by those behind its creation as an improvement over the traditional-sized (and troubled) Eisenhower dollar.

Unfortunately, the first small dollar was a spectacular failure the likes of which the Mint hadn’t seen since the twenty cent piece of 1875-1878. The coin had the misfortune of combining an odd shape and drab design with the weak purchasing power of the dollar and post-Vietnam malaise. To top it off, many people saw the design as a cynical and politically-correct sortie to advocate for partisan politics on the country’s money while attempts to ratify the Equal Rights Amendment were being made across the land. At any rate, it probably doomed radical innovation in United States coinage for decades to come, thus putting the seal on the Modern Era.

Unfortunately, the first small dollar was a spectacular failure the likes of which the Mint hadn’t seen since the twenty cent piece of 1875-1878. The coin had the misfortune of combining an odd shape and drab design with the weak purchasing power of the dollar and post-Vietnam malaise. To top it off, many people saw the design as a cynical and politically-correct sortie to advocate for partisan politics on the country’s money while attempts to ratify the Equal Rights Amendment were being made across the land. At any rate, it probably doomed radical innovation in United States coinage for decades to come, thus putting the seal on the Modern Era.

THE POSTMODERN ERA BEGINS

When considering a shift in eras, such as between Modernism and Postmodernism, it is important to note that “eras” never start and stop cleanly; there is always a transitional period. In terms of determining the shape of the Postmodern period, we feel that the Susan B. Anthony dollar is important. Not because of its failure or even its bizarre concept, but for the change in numismatic vision that it exposed. Hence, it straddled the boundary between the two worlds.

Its disappearance after 1981 is the perfect segue into the Postmodern Era, as the first truly Postmodern American coin – the 1982 George Washington 250th Anniversary commemorative half dollar – was produced the following year. The mint was so involved in the production of the new commemorative coins (over seven million minted) that they had no time to put together 1982 mint sets. By the time mint sets resumed in 1984, the decision had been made to no longer produce the Susan B. Anthony dollar – not even for collectors.

The “modern” commemorative program (as it’s called), has been rightly criticized over the years as being over-produced, overpriced and underwhelming to look at. On a case-by-case basis, each of these critiques is fair. The current program, unlike the classic one that ended in 1954, was centralized, and the Mint was in complete control of distribution. And to avoid the tomfoolery, corruption and boredom that brought an end to the first program, the new commemoratives shunned regionalism and honored only subjects pertinent and appealing to the nation as a whole. It was during this period, starting in 1982 and running through the mid-‘90s, that the Mint did the market research that led to the boldest and most daring coin program in its history – the 50 State Quarters program.

This program saw a redesign of the quarter’s reverse and the creation of a public spectacle surrounding the release of each new design. The program was a huge PR and financial success for the Mint, bringing in much-needed revenue (the Mint had become a Public Sector Enterprise in 1995, responsible for its own operating costs; this, above all else, caused it to take such a consumer-oriented stance and produce the dizzying array of coins, medals, novelty gift sets and commemoratives we see pouring out today). The program also brought in a record number of new collectors to the hobby, incidentally.

This program saw a redesign of the quarter’s reverse and the creation of a public spectacle surrounding the release of each new design. The program was a huge PR and financial success for the Mint, bringing in much-needed revenue (the Mint had become a Public Sector Enterprise in 1995, responsible for its own operating costs; this, above all else, caused it to take such a consumer-oriented stance and produce the dizzying array of coins, medals, novelty gift sets and commemoratives we see pouring out today). The program also brought in a record number of new collectors to the hobby, incidentally.

These fresh collectors were excited by the immediacy of the new quarters – this sped-up release schedule for new designs was unheard of. In order to maintain the tempo, the Mint brought in new artists and engravers, including several from the Franklin Mint.

The infusion of all of this new talent resulted in a new artistic style. This style has come to define the Postmodern Era of American coinage. It borrows from the past, sometimes to the point of caricature. It’s not designed to make an artistic statement for the ages or serve as a symbol of economic and political might. Instead, it strives to be self-referential, with the purpose of educating Americans about America. Gone are visions of the ideal of Liberty, and we’ve arrived at a seemingly endless cavalcade of tourist destinations and clichés.

But speaking of the Franklin Mint (a Postmodern institution if ever there was one), the recently public-sectored U.S. Mint sought to protect itself from such third-party competition. So to prevent other companies from honing in on the lucrative State Quarter market with “unlicensed” product, the United States Mint trademarked the designs.[3] An unusual move, and one that seems to run contrary to the spirit of a government of the people, by the people, and for the people.

(Why did this particular golden goose need such protection? Because the State Quarters program was designed with hoarding in mind. Every state quarter hoarded is money (seignorage) in the bank, pun very much intended).

Another consideration as to what ultimately delineates the Modern from the Postmodern Era, is how the coin hobby began to focus on the grades of coins, and the subsequent rise of the third-party grading companies in the mid to late ’80s. A circumstance made possible only after the widespread acceptance and refinement of the Sheldon Scale for all coin series, first introduced in reference to large cents in Sheldon’s classic Early American Cents (1949). Up until then, collectors had broader definitions for circulated and uncirculated conditions. So before the TPGs, no real hobby-wide effort was made to save the best coins.

In the Postmodern period, however, only the best specimens are worthy of consideration. For some series, MS-67 is considered low-end.

In the Modern Era, finding coins as good as MS-65 required some work. For other series, MS-66 was as high as you could expect to find after putting in some serious effort, and the anomalous MS-67 coin would be so scarce as to command premiums of hundreds or thousands of dollars for even common dates. In the Postmodern period, perfection or near-perfection is expected, and the long term implications are that a significant number of these types of coins will be saved and encapsulated forever. For coins of the Modern Era, collectors have been afforded no such luxury.

WHAT THIS MEANS FOR THE HOBBY

When we undertook this topic, we knew that it would be critical to answer the question, “What does this mean for me?” The answer to that question requires very little imagination. Collectors have long understood that what is of the past remains in the present for only a short while. Just as Indian Head cents eventually faded into obscurity and out of pocket change by the 1950s, so too will the coinage of the Modern Era.

* * * *

Our advocacy work for modern coinage is no secret, but it’s not a totalizing bias either. Few can argue against the beauty of America’s classic coins, from the Bust Liberty patterns and Gobrecht’s soaring eagles, to Saint-Gaudens and company’s beautiful turn of the century rejuvenation of U.S. coin design. While we might disagree about whether the Modern Era reached or even aspired to that level of artistic merit, we should all be able to see that which is plainly in front of us.

The Modern Era of United States coinage has passed.

We are now in a Postmodern age.

FLIP OF A COIN:

More about Columbia: Before she was supplanted by the Statue of Liberty, the quasi-mythical Columbia was the figurative embodiment of America and her ideals of Liberty. The newly-hewn district, within whose borders the federal city of Washington was founded in 1791, was named the District of Columbia in her honor. Inspired by the conquest of a continent, the commemorative half dollar issued during the Panama-Pacific International Exposition bore her image.

Good Grief: Universal Coin & Bullion took out a back cover ad in the June 2012 issue of Coin World advertising an offer wherein first-time customers can order specially-slabbed silver American eagles. What’s so special about them? They come graded from the first fifty boxes of the coin that NGC opened. The ad says, “The ‘First 50 Boxes’ of 2012 Silver American Eagles will definitely be a small and exclusive group”. Well, sure it will… and an entirely arbitrary one at that!

Most coin collectors are familiar with the change in composition of the Jefferson “nickel” five cent piece during World War II. But were you aware that the oversized mint marks placed above the rotunda were designed for the sole purpose of allowing the Treasury Department to remove the billon coinage from circulation once nickel coining resumed? Talk about planned obsolescence.

* * * *

REFERENCES:

http://typesets.wikidot.com/france:1-franc-1898-1920

http://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/ws/index.php?pid=14611&st=&st1

Moran, Michael. Striking Change: The Great Artistic Collaboration of Theodore Roosevelt and Augustus Saint-Gaudens. Whitman, 2008. Print.

http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/0/0c/Houdon_bust_of_Washington_at_Mount_Vernon.jpg

Yeoman, R. S. A Guide Book of United States Coins 2013. Whitman, 2013. Print.

Sheldon, William H., Dr. Early American Cents, 1793-1814 An Exercise in Descriptive Classification with Tables of Rarity and Value. Harper and Brothers, 1949. Print.

[1] Brown, Vernon L., ed. Selections from the Numismatist: United States Coins. Racine, WI: Whitman Publishing, 1960. Print.

[2] Petry, Sam. Phone Interview with Charles Morgan, 8/15/2012