by Walt Ostromecki, NLG – The California Numismatist

Forward

According to early Southern California lore and legend, there lies a fortune in gold ore, bars and coins still buried deep in the cold murky mud on the ocean bottom of the San Pedro Bay. Much of that gold ore came from the booming mines located in the eastern Mojave Desert and throughout the San Bernardino mountains.

Written accounts at the time of this early Los Angeles “golden treasure tale” read more like a Hollywood movie script complete with mystery, intrigue, murder and a missing treasure — something which might have been written for an episode of one of those old weekly wild-west TV shows from the 1950’s and 60’s such as “Have Gun Will Travel”, “Death Valley Days”, or that combined history legend- based western classic of classics’ series “Tales of Wells Fargo” starring Dale Robertson — rather than any factual account of the true events which took place in San Pedro Bay nearly 150 years ago, when the legendary wild west was very much alive.

Written accounts at the time of this early Los Angeles “golden treasure tale” read more like a Hollywood movie script complete with mystery, intrigue, murder and a missing treasure — something which might have been written for an episode of one of those old weekly wild-west TV shows from the 1950’s and 60’s such as “Have Gun Will Travel”, “Death Valley Days”, or that combined history legend- based western classic of classics’ series “Tales of Wells Fargo” starring Dale Robertson — rather than any factual account of the true events which took place in San Pedro Bay nearly 150 years ago, when the legendary wild west was very much alive.

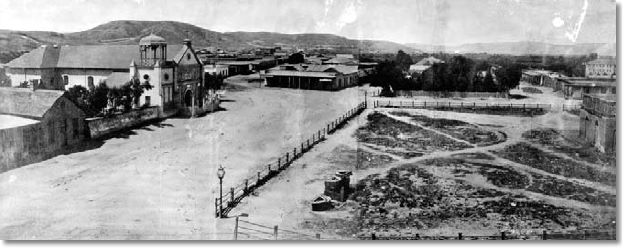

Back in the late 1850’s and early 60’s, most of the Southern California landscape which surrounded Los Angeles was a hot, dry, sage-scrub chaparral surrounded by rugged mountains which gave way to an even harsher, drier and foreboding extensive desert region. This raw, wild and woolly western frontier was hardly suitable for homesteaders, towns, agriculture, cattle ranching, or much of anything.

The tiny, sleepy pueblo of Los Angeles had an approximate population of around 6,000. It’s two, tiny, outlying coastal seaport and commerce towns of Wilmington and San Pedro had a combined population total of about 700. The large commercial seaport city of modern Long Beach with its massive harbor and freight distribution center was not even as yet on the map.

Preview From Our Wild-West Wells Fargo Adventure

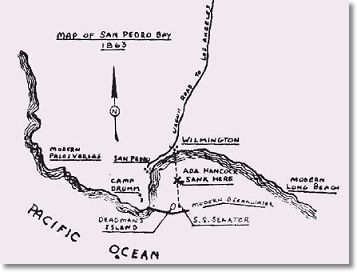

A few minutes before five o’clock on the chilly evening of April 27, 1863, with 55 passengers and all freight aboard, Captain Seeley ordered the bow and stern lines of the ferry Ada Hancock cast off. She began to move slowly away from Banning’s Dock at Wilmington (in what is present day Long Beach Harbor) and out into the gray waters of San Pedro Bay. She was headed for the SS Senator anchored about two miles away.

At precisely 5PM, and midway (about one mile) through her short voyage the Ada Hancock was suddenly blown apart by a terrific explosion. The big ferry instantly sank in a fiery ball of flames, leaving only debris, bodies and thirty dazed survivors floating in the water. Whatever freight and fortune in gold and coinage she was purported to be carrying sank deep into the murky mud of San Pedro Bay.

Printed news stories at the time of the incident read more like a Hollywood movie script than a true and factual accounting. Tales of treason, conspiracy and a vast “purported fortune in gold,” both bars and coins, aboard the ferry sprang up the very next morning following the Ada Hancock disaster.

Local residents of the nearby sleepy pueblo of Los Angeles, population about 6,000, and its tiny port towns of Wilmington and San Pedro, spun disaster survivor accounts into a Wells Fargo and Company story of machination, robbery, murder and the vast loss of a golden treasure valued into the hundreds of thousands of dollars. But, that was a time when the legendary “old west” in Southern California was very much alive.

The Adventure Begins

Our San Pedro Bay gold treasure mystery saga and historical tale of Wells Fargo opens in the “old wild west” of Los Angeles, California, in the year 1859 with the dawn of a burgeoning economy that had just awakened this once sleepy little pueblo — thanks in part to the rich gold strikes in the mines of the Holcomb Valley, the Mojave Desert, and others eastward through the San Bernardino mountains to the Colorado River.

It also involves the two, tiny, nearby port towns of Wilmington and San Pedro, where two competing stage and freight lines owned by Phineas Banning and John Tomlinson served the harbor ports and the enormous inland dry chaparral-desert area extending as far as 250 miles from the coast where gold mining was the economic base. But their services were minimal at best. They both lacked the ability to handle large commercial freight services, dependable employees and shipping schedules, adequate security measures for the transportation of raw gold ore, and a safe and secure place to house it once it reached the coast, because there was no banking house.

A far more reliable and secure banking house with commercial and transportation services was needed. Wells Fargo and Company fit that bill. They had already created many banking outposts of security, integrity and civility across the western United States. They were also the first in many cases to establish offices where even the US mail wouldn’t deliver, making it possible for miners and others to not only exchange raw gold dust and nuggets, but to conduct banking transactions, reliably send and retrieve mail parcels and freight, and meet family, friends and business associates arriving on overland stagecoaches.

After the financial panic of 1855, Wells Fargo and Company, like its major competitors, emerged in a strengthened position. It began to establish a number of new branch banking offices in important western towns such as: Shasta, 1856; Yreka, 1857; Victoria, BC, 1858; and Los Angeles, 1859.

However, the Los Angeles economy around the outset of the Civil War took a sudden nosedive and became so bad that Wells Fargo closed its banking house there in 1862. Only its Express Office and Stage Line operations remained. From late 1862 to early 1866 no major banking house operated in Los Angeles.

Because many of the residents in Southern California were secessionists with sympathetic loyalties to the Confederacy, the US Army established a large seaport garrison at “Drum Barracks” in Wilmington. From there, the military-escorted Wells Fargo freight wagons moved massive amounts of military supplies inland to Forts Tejon, Mojave, Camp Independence, Yuma and several other small outposts.

Because many of the residents in Southern California were secessionists with sympathetic loyalties to the Confederacy, the US Army established a large seaport garrison at “Drum Barracks” in Wilmington. From there, the military-escorted Wells Fargo freight wagons moved massive amounts of military supplies inland to Forts Tejon, Mojave, Camp Independence, Yuma and several other small outposts.

On the return trip, the wagons and stages carried large amounts of gold dust to the busy Wells Fargo banking office in Los Angeles. The office also received and housed gold bullion, bars, and raw ore from the rich strikes in the San Bernardino mountains adjacent the Holcomb Valley mines, the central Owen’s Valley, and even the Laguna de la Paz along the Colorado River.

Working out of the bustling Los Angeles Wells & Fargo Express Office were several bonded messengers who were entrusted to carry large amounts of gold, coin, currency, bonds and stocks between that city and San Francisco, both overland and on coastal ships. These long-time trusted couriers were paid $75 dollars a month for their services. Two, Louis Scheslinger and William Ritchie, are involved in this golden story.

Louis Scheslinger was a crafty scoundrel with few honorable character principles. Unbeknownst to Wells Fargo, he had established a lucrative sideline business “as an extortionist and loan shark where he could charge exorbitant interest rates (at 50% and above) to small landowners who could not qualify for a normal bank loan.” He was ruthless and would foreclose on the due date of any outstanding mortgage and immediately seize the land, an act that made him increasingly wealthy and very unpopular. Yet for some reason when Wells Fargo got wind of his actions, they turned a deaf ear to it.

In July of 1862, Scheslinger made a one-year loan of $30,000 dollars to Don Ricardo Vejar. For collateral Vejar put up his extensive Spanish land grant east of Los Angeles. A clause in the mortgage stated ‘total amount due immediately in the event of Vejar’s death’. On the morning of April 20, 1863, Vejar was thrown from his horse and instantly killed. Even before his family could bury him, Scheslinger accompanied by two armed thugs arrived at the ranch. He demanded full payment of the thirty grand with interest from his eldest son, Ramon, or “I’ll take immediately ownership of the entire ranch.”

Ramon thought the demand “of loan shark” Scheslinger was totally unreasonable and without merit, but quickly learned he was deadly serious. He thereupon picked up the mortgage documents and excused himself from the room. After a short wait, the three scoundrels realized he wasn’t coming back. Their ears noticed the noisy ranch activities had ceased. As they peered through the ranch house windows to the outside, they noticed the ranch was now completely deserted. Ramon, his family and all the hands — and nearly every animal — had disappeared.

Fearing the worst for their safety, the three rogues with guns drawn discreetly rode off in a big hurry. As they galloped along the dusty trail talking “trash” amongst themselves, Scheslinger became increasingly angry and vowed to return with the sheriff and officially take possession of the ranch. As the trio hurriedly, yet cautiously, rode down into a small ravine, a series of gun shots rang out. One of the two accompanying gunmen was instantly killed and the other seriously wounded. Scheslinger somehow managed to escape without a scratch.

Arriving hot and sweaty in Los Angeles, a stoic Scheslinger reported the ambush to an unsympathetic sheriff who declined to investigate the matter nor take any action against the accused Vejar family. And none was ever taken.

Now fearing for his life and continually looking over his shoulder, Scheslinger began to liquidate his entire mortgage holdings at up to a 50% discount. On the morning of April 27, 1863, he sold the Vejar and several other mortgages to Robert Clark, a Los Angeles financier, who paid him cash. The two met at the Wells Fargo (banking) office and concluded their business transactions there in the lobby. Afterwards, Scheslinger also closed out his personal accounts as well for cash and gold coins. The total amount was said to be just more than $100,000.

Later that same afternoon, Scheslinger was observed having a conversation with his co-worker, William C. Ritchie, in the lobby of the Belle Union Hotel. They were again both seen together outside the Wells Fargo office around 3PM on horseback with filled saddle bags, riding out of town in a southerly direction (toward the Wilmington Docks). Around 4PM, the telegraph between Banning’s Wilmington dock and Los Angeles, twenty miles away, suddenly went dead. Hours later it was discovered the wires had been cut on the south road near the midway point between the two stations.

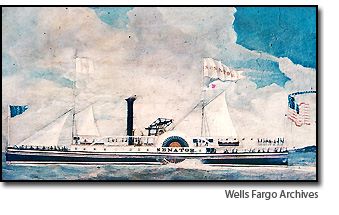

At around the 4PM time line, the coastal steamship, the SS Senator anchored near Dead Man’s Island in the San Pedro Bay, was making preparations for its 5PM departure to San Francisco. The ship was forced to anchor a couple of miles offshore because its size made it impossible to cross the shallow sand bars in the harbor and reach the Wilmington Dock. Freight and passengers had to be shuttled between the dock and the ship by small shallow draft ferries. One of these was the relatively new ferryboat Ada Hancock.

At a few minutes before 5PM, with 55 passengers and all freight on board, Captain Seeley ordered the bow and stern lines cast off. The Ada Hancock began to slowly pull away from the dock. At that same moment, Scheslinger dashed up on a lathered horse and loudly demanded to get on board. The captain reversed his vessel and Scheslinger was able to jump off his horse and aboard the ship.

The Ada Hancock again moved ever so slowly away from the Wilmington dock and picked up speed. She steered directly across the murky, gray water toward the SS Senator anchored about two miles away. About midway on her short voyage, and at precisely 5PM on the chilly evening of April 27, 1863, the Ada Hancock was disintegrated by a devastating explosion that was heard for miles around. She instantly sank into her watery grave there at the bottom of the silty-muddy San Pedro Bay, leaving only floating debris, bodies and 30 cold, wet, and dazed survivors.

The SS Senator immediately came to the rescue. Its crew quickly lowered its life boats and began to pick up survivors thrashing about in the water. Soldiers from Camp Drum soon joined in. They also heroically rescued survivors and recovered the floating bodies of the dead. Many of the 30 survivors lived through the tragedy because of the quick emergency medical attention provided by the doctors and staff at the military hospital. A few of the

uninjured ones taken aboard the SS Senator stayed on and made the trip to San Francisco.

Word of the Ada Hancock disaster did not reach Los Angeles for more than four hours as the telegraph wires had been cut earlier that afternoon. When word did and the story was finalized, it was learned that many of the 26 who perished were prominent well-known community leaders. Los Angeles was both shocked and stricken by the senseless loss of life.

Counted among the dead was William Sanford, Phineas Banning’s father-in-law, a major player in California transportation. He led the first commercial wagon train in 1859 from San Pedro to Salt Lake City, UT, with 15 wagons carrying 50,000 pounds of merchandise, each drawn by 10 mules. He was also with the group who scouted the 1861 route and built the first road east from the Cajon Pass to Holcomb Valley. In July of 1861, he personally hauled the first 8,000-pound Mellus stamp mill boiler over the new road to an ore mining and refining camp in the Holcomb Valley.

Benjamin D. Wilson, pioneer of pioneers who discovered and named Bear Valley (in the San Bernardino Mountains above Lake Arrowhead) was also on board the ill-fated ferry with his daughter, Sue, and his wife’s sister, Medora Hereford, were both seriously injured. Medora, who was seriously burned over more than 70% of her body, died of infection in the Camp Drum hospital in Wilmington three months later. Wilson was already depressed by the Civil War and the recent death of another daughter, Maggie. The death of Medora and the long recovery proved too much for him. He could barely function. His insanity drove him to kill himself shortly after Medora’s death.

The Disaster Aftermath

News wire reports surrounding the loss of the ferry Ada Hancock in San Pedro Bay went out as soon as possible to newspapers throughout California, just hours after the disaster. Bold typeface headlines in San Francisco, Sacramento, and a multitude of other California and Nevada newspapers reported the story as follows:

“$100,000 in gold and silver reserves stolen from Los Angeles Wells Fargo Office,”

“Vast gold and silver treasure lost in San Pedro Bay ship disaster,”

“$125,000 in missing funds entrusted to Wells Fargo Agent Ritchie for transportation to San Francisco,”

“Vast golden treasure mysteriously vanishes which was secretly brought aboard anchored San Pedro Bay Hancock ferry in three medal boxes containing 700 ounces of gold, coin, bars and dust (a cool near three quarters of a million dollars worth by today’s market value). Wells Fargo investigates loss,”

“Wells Fargo messenger killed. Fierce gun battle breaks out aboard ship. Explosion sinks Hancock. Foul play suspected in $100,000 gold theft,” and “Murder mystery surrounds Wells Fargo agent and loss of $100,000 in gold aboard ship.”

The day after the Ada Hancock disaster, a newspaper headline reported:

“Wells Fargo agents discover Messenger Ritchie took not only the authorized $25,000 in gold for transport to San Francisco, but the entire reserve of $100,000,” [Note: This led some newspaper stories to report the total gold loss at $125,000 dollars.]

“Fallout among conspirators leads to double-cross, a shoot out and explosion aboard ship carrying vast amount of gold,”

“Plot thickens in Wells Fargo robbery and murder investigation of Hancock sinking.”

Three days later San Francisco newspaper headlines read:

“Body of Wells Fargo Messenger Ritchie washes ashore three days after Hancock disaster.Whereabouts of missing gold treasure unknown.”

The Official Investigation

In the investigation which quickly followed the Ada Hancock disaster, Well Fargo agents who interviewed survivors recorded that many reported “gunshots had been fired” on board the ferry just before the horrific explosion took place. There were conflicting reports as to whom was involved here, though some did recall seeing both Ritchie and Scheslinger with a couple of other men on the ship. Neither Ritchie’s body nor that of Scheslinger was not found among the dead, which was strange.

Wells Fargo agent interviews with the freight loading crew added yet another strange twist to the growing intrigue surrounding this case. Two of them recalled and insisted that when Ritchie arrived at the dock in the late afternoon, “he unloaded not one, but a total of three heavy metal boxes which were placed on the deck of the Ada Hancock next to several barrels of gun powder.”

Public speculation and rumors ran rampant that “the two had somehow conspired together to steal the three boxes of gold…(then) managed to mysteriously make it off the ship alive carrying the heavy metal boxes…and tried to cover up the theft by blowing up the ferry…”

This widespread public theory was the talk of the town and the telegraph. When Ritchie’s body mysteriously washed ashore near Banning’s Dock three days after the disaster, rumors became fact. They quickly surmised and spread the word that Ritchie and Scheslinger were partners in the theft of gold coin and bullion from the Los Angeles Wells Fargo bank office, and that Ritchie at the last minute had tried a double-cross which resulted in a gun battle on board the Ada Hancock and caused the ensuing disaster.

Oddly enough, the water bloated and intact corpse of Ritchie showed no signs that it had been in an explosion and in fact was still wearing his favorite gun holster, but the weapon was missing! The body of Scheslinger was never found at the time, which only added more fuel to the mystery fires of intrigue surrounding what was reported “as the largest gold theft of the time from Wells Fargo.”

Subsequently, Wells Fargo investigators in possession of all the facts concluded otherwise: “…although in all probability a gun blast did trigger the explosion which resulted in the destruction of the ferry, there is no corroborative evidence to support the claim of a gun battle between the two took place on board the ferry nor the fact the Messenger Ritchie carried more than one metal box aboard the ferry containing less than $500 dollars in coin and 52 ounces of gold dust…”

Did the supposed mysterious gun battle between Ritchie and Scheslinger actually take place, or is it just another of the tales spun to add spice, mystery, and intrigue to the unfortunate explosion which sank the Ada Hancock? And furthermore, is there any truth to the story that a fortune in Wells Fargo gold bullion and gold coin was even involved here? Or, it is another exaggerated legendary tale of the old west? And, what about the missing body of

Scheslinger?

Well, according to factual records of the day provided by Wells Fargo and Company’s San Francisco archivist and historian, Robert Chandler, the following are the facts in this case dealing with Messenger Ritchie and the gold.

Fact #1 – “Wells Fargo records show there was no Wells Fargo bank or facility with $100,000 in assets, gold or otherwise, in Los Angeles at the time of the Ada Hancock’s demise in 1863.”

Fact #2 – Wells Fargo closed down its Los Angeles banking house in 1862. A Mr. Louis Hellman, banker, did not begin his banking operation there until early 1864.

Fact #3 – Wilmington did not have a bank and there was no banking facility in that area until one was opened in San Pedro in 1888.

Fact #4 – No Bank in the Los Angeles region had or stored gold assets of $100,000 in 1863.

Fact # 5 – Messenger Ritchie and Mr. Scheslinger were acquaintances. Both knew each other and both worked at times for Wells Fargo, and were in Los Angeles at the same time, on the same day of the Ada Hancock disaster. Eventually Wells Fargo investigators determined that the two were indeed partners in the theft of the authorized gold from the bank which Messenger Ritchie was entrusted. Furthermore, Ritchie had tried a double-cross at the last minute ending in the on board gun battle that probably triggered the explosion on the Ada Hancock.

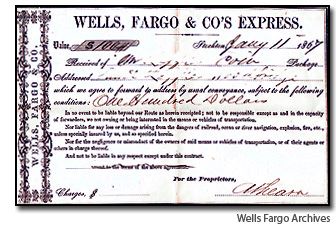

Fact #6 – “Wells Fargo Messenger Ritchie was scheduled to take charge of only one iron box containing 52 ounces of gold dust and $574.40 in coin and paper to San Francisco that day aboard the SS Senator. Records further note the dust came from Fort Yuma merchant and Colorado River gold dust-buyer, George F. Hooper. Wells Fargo records.”

Fact #7 – Cash books of the day reveal Wells Fargo lost a total $308.78 in coinage with the sinking of the Ada Hancock, $42.96 of which was being sent to San Francisco to purchase an Eastern draft for a client and $265.62 from collecting a debt in Los Angeles. Period!

Fact #8 – “There is absolutely no mention in our claimed insurance records that corroborated Wells Fargo losses were either $25,000, $100,000 or $125,000. These figures only appear in newspaper accounts.”

Fact #9 – In 1865, the California State Supreme Court, Hooper V. Wells Fargo 27 Cal 1865: 11-49 affirmed “Wells Fargo biggest financial loss in the Ada Hancock disaster was $10,755 dollars, the value of the 52 ounces of gold dust (at the then-current value of $20.96 an ounce) which Messenger Ritchie carried inside one iron box, and the cash book records for an additional $308.78 in coinage — the $42.96 for the Eastern draft and the $265.82 in cash from the collection of a debt. Wells Fargo in court with papers claimed that as it did not run the steamboat, it was not liable to pay the insurance claim to Mr. Hooper. But, the Court deemed them ‘as a common carrier’ and therefore they were!”

Fact #10 – In the March 25, 1895 issue of the San Francisco Bulletin which discussed at length the “common carrier clause” court ruling against Wells Fargo and the papers relating to their appeal of the case, give no indication of their loss amount total being greater than $11,063.78 dollars.

Fact #11 – No attempt to recover the gold dust and coin from the 1863 shipwreck of the Ada Hancock was ever made, and if the real amount was as claimed, $125,000, surely Wells Fargo would have long ago claimed all (future) salvage rights to any express boxes brought up from the San Pedro Bay filled with gold, or made a serious effort at the time or even now to recover it.

Fact #12 – The case was “marked closed” by Wells Fargo and Company in 1865, but the speculation and legend purporting a vast lost golden treasure on board the Ada Hancock in 1863 persists today. There are some who still believe $125,000 in gold lies in the silty, muddy, watery grave at the bottom of San Pedro Bay; it grew and grew into what the author in jest calls “….just another of the many Tales of Wells Fargo.”

Fact #13 – There is absolutely no truth to the rumor that the fortune in purported stolen gold made its way secretly to the Confederacy, without some written record somewhere being kept.

Fact #14 – In 1912, the Wells Fargo “golden mystery tale” surrounding the 1863 explosion and loss of the ferry, Ada Hancock, was front page news again. A new building foundation was being excavated near the site of the long since vanished Banning Dock. A skeleton of a large tall male was unearthed. The Los Angeles coroner’s office carefully examined the remains. It was determined that death was from a single bullet that entered the middle of the skull and that death had occurred so far back in time that no further investigation into the matter was ever made. The only identification found with the skeletal remains was a heavily corroded belt buckle with the initials “LS.” Louis Scheslinger?

Wells Fargo long ago may have paid the insurance claim on the gold dust and officially closed the case, but the California newspapers in 1912 concluded otherwise — “the mystery of the Wells Fargo Ada Hancock gold robbery of 1863 still goes unsolved even after the remains of the coconspirator, Mr. Scheslinger, are unearthed near the old Banning Dock in Wilmington.” But, where’s the gold? This only furthered the mythical legends built up by the residents of the city of Los Angeles following the horrific sea disaster of the Ada Hancock in San Pedro Bay.

Epilogue

Is there any truth to the sensationalized old west accounts that there is still indeed a vast gold coin depository of hidden Wells Fargo treasure deep down in the San Pedro Bay today? Or are they all just legends, embellished, puffed up and spun fabrications laced with tidbits of mystery, intrigue, mayhem, and intrigue, thus making our vast golden treasure story nothing more than an intriguing wild west tale and hoax?

Sadly, this seems to be the case. Documented facts conclude with a 99.9% certainty that the purported stolen and never found $125,000 in Wells Fargo gold and coin is nothing more than a masterfully spun hoax, devised and perpetuated by the Los Angeles’ wild west folk town to draw attention to their sleepy little pueblo! But why?

The answer is at least two-fold: First, what better way for the city of Los Angeles to earn an everlasting place in early California history and Wells Fargo lore as well. And second, what better way to entice and attract visitors to the pueblo who would spend money there: settlers, businesses, financiers, and others to come as well and make the city their home and establish new businesses and invest in industry and commerce — the latter specifically to Los Angeles as another major port and trade center in California to rival that of San Francisco. And, it worked. Today, Long Beach is the second busiest major harbor-port city in the nation!

The Numismatic Epilogue And NASC Postscript

Ah, but, then there’s still that .1% unresolved gold coin treasure “doubts factor”. Not much I grant you, but it deserves to be addressed. It says to us mystery lovers that our wild west Wells Fargo golden treasure story adventure is in fact a true unsolved mystery in the annals of Wells Fargo.

So, based on that minute .1% premise, what sort of “numismatic gold coin treasure” could a salvager (say financially underwritten in part by collectors and members of the NASC) today expect to recover from the deep muddy waters in the San Pedro Bay?

After all, the 1863 value gold was placed at $125,000 when gold traded at approximately $21 an ounce. But today in 2010, that old gold value translates into a cool $26 million (before taxes) with the gold market rate at roughly $1,200 dollars an ounce, one excellent reason for the NASC and its member numismatists to give serious thought.

So, what historic and classic numismatic coin (both gold and silver) rarities or gems might be unearthed and recovered from the site of the old Ada Hancock disaster in the San Pedro Bay?

Well, let’s concentrate our numismatic efforts on those coins, gold and silver, that would likely be among the $574.40 in Messenger Ritchie’s metal box in 1863. We will also only consider those produced at the S, O, C, D mints:

A) $20 dollars – 1861-S Paquet Reverse, any 1854-61 O Mint pieces

B) $10 dollars – 55-S, 58-S, 59-S, 60-S

C) $5 dollars – any C and D gold issues from 1839-61; 1858-60-S coins

D) $3 dollars – pick any C, D, S, issue from 1854

E) $2.50 dollars – the 1848 “Cal”; any C and D issue

F) $1.00 dollar – all C and D issues, particularly 1860 and 61- D’s.

Silver dollars – 1859-S. Minor coinage: 1853-O Half, no arrows; 1859-60-S Quarters; 1856, 58 and 59-S dimes; and 1863-S half-dime.

Why, one silver 1853-O half without arrows alone graded VF in the 2010 Red Book is valued at $400,000 dollars while an 1861-S $20 Paquet Reverse is at $2 million. The $2 ½ “Cal” gold in VF runs $28,000. Believe it or not, just one recovered $20 gold piece in low grade condition would today be a little over twice the total content value within Messenger Ritchie’s box in 1863.

Enough! Realities check. Ah, but alas this is only the author’s wild imagination, a dream being spun into just another “wild overly-embellished gold tale” — something certainly not worthy of a new chapter in the historical saga surrounding the Ada Hancock disaster nor an early western episode in the on-going Tales of Wells Fargo!

Credits:

Robert Chandler, Historical Services, Wells Fargo Bank, 420 Montgomery Street, San Francisco, CA 94163.

The Sunken Treasure Literature Club, (an ANA member club), Clarendon Hills, IL 60514

On The Mountain, a Lake Arrowhead independent monthly magazine. February/March 2001 issue, Holcomb Gold and Disaster.

I read the article in California Numismatist titled, ‘A Gold Coin Treasure in San Pedro Bay? – or – Just Another Tale of Wells Fargo?’ and have spotted an error, although the error has nothing to do with conclusions drawn by the author as to the disappearance of the gold. His error was in citing that Benjamin D. Wilson committed suicide shortly after Medora died. Medora died in 1863 shortly after the Ada Hancock disaster. Benjamin Wilson did not die until March of 1878 at the age of 66 of a heart attack Benjamin Wilson, himself, wrote just before his death the following: “Hope to pass the remainder of my days in peace with God and man, as well as with myself.” Signed by B,. D. Wilson Dec. 12, 1877.