By Dariusz F. Jasek …..

Link to Part 1

About a century before the birth of the Netherlands gold ducat, many different gold coins were in circulation in the Low Countries and neighboring lands. Various coin types were usually minted strictly for specific purposes: e.g. goldguldens were usually minted for trade with Germany, while gold reales were minted primarily for trade with Spain. In other words – a uniform, consistent and widely accepted coin type was missing.

The situation was made even more complex when identical coins were compared to the same coins in various countries because their names were often used interchangeably. In one country the coin was called a gold ducat, while in another country exactly the same coin could be called a florin or goldgulden. A coin minted with the same weight and fineness was lacking in many countries.

This inconsistent money was difficult for money changers, who had to recalculate the gold content in every coin type they dealt with. Independence from Spain brought to The Netherlands a need to create a good and stable trade money (read more in Part 1, above). The Netherlands gold ducats quickly became very popular throughout Europe, primarily because of their unchanged weight and fineness, which was contrary to other gold coins circulating at the same time in various European countries.

There is a well-known principle which says that when two kinds of money considered equal in legal terms (face value) circulate at the same time, the better (e.g. of a higher fineness) money will be hoarded by people, and the mainly “worse” inferior money (e.g. debased, truncated, or just false coins) will remain in circulation. Put succinctly, bad money always drives out good money from circulation. This rule, which became commonly known as Gresham’s Law, was first documented around 405 BCE in the The Frogs, a play written by Aristophanes. Indeed, the fineness of precious metal used for minting coins – silver and copper in particular but sometimes even gold – was often lowered at various times by issuing authorities to gain more profit from minting.

But the weight and fineness of gold ducats, minted in the Netherlands and other countries, remained unchanged over time.

However, the value of a ducat was always increasing. Over short periods of time they were usually just small increases in their value, but there were some exceptions. For example, when comparing the value in 1574 to the value from 1606, the value of a ducat in the Low Countries was about doubled. A similar situation took place in Poland between 1619 and 1628 – the value of a ducat also almost doubled.

While the Netherlands only minted single and double ducats, many European countries followed the Dutch idea and minted their own single and double gold ducats. But some of them minted larger multiple ducats as well as ducat fractions. Meanwhile there were even 100 ducats coins struck by some other countries. In Poland for example, under King Zygmunt III, a large number of types of the 100, 90, 60, 50, 40, 20, 15, 10, 9, 8, 5, 4, 3, 2, 1, and ½ ducat were minted. On the other hand, the Nuremberg mint (Germany) minted fractions of one type of a gold ducat – the undated one with the Lamb of God on globe – as ½, ¼, 1/8, 1/16 and 1/32 of a ducat. All of that was due to the unprecedented success of the Netherlands ducat.

For understanding how large the 100 ducats coin was, we may compare it to the round Lamb of God half ducat found here. The diameter of the Polish 100 ducats piece was about 70 mm, 4.1 times more than the diameter of the round Lamb half ducat, and the thickness of the 100 ducats piece was 4.9 mm – it weighed 200 times as much!

In the Low Countries the first gold ducats were minted in the second half of the 16th century by a number of mints and with varying fineness. Many types of those early ducats were minted with pictures of Saints on the coin. Double ducats with St. Stephanus were minted in the Batenburg and Nijmegen mints. Single ducats with St. Victor were struck in Batenburg, St. Oswald in ‘s-Heerenberg and Stevensweert, St. Pancras in Hedel, St. Stephanus in Nijmegen and with St. Henricus in Vianen.

In addition, an imitation of the Salzburg ducat with St. Martin was also minted in Hedel. The only rare double ducat with Jesus Christ and Pharisee, pictured below, was minted at the Batenburg mint.

The Batenburg undated double ducat with Jesus Christ and Pharisee. Teylers Museum, inv. no. TMNK 07389.

Gold ducats with Saints: the ‘s-Heerenberg ducat with St. Oswaldus (top)

and the Hedel ducat with St. Pancras (bottom). Teylers Museum, inv. no. TMNK 07639 and TMNK 07663.

Provincial mints minted well-known single and double ducats of the Dutch type in 12 cities:

- The Gelderland mint (in Harderwijk)

- The Holland mint (in Dordrecht and for a short time also in Enkhuizen)

- The West Friesland mint (in Hoorn, Enkhuizen and Medemblik)

- The Zeeland mint (in Middelburg)

- The Utrecht mint (in city of the same name)

- The Friesland mint (in Leeuwarden)

- The Overijssel mint (in Kampen)

- The city mints of the Imperial cities (in Deventer, Kampen and Zwolle)

- In 1673, due to the war, the Holland gold ducats were exclusively minted in Amsterdam. But even then, the mint followed the .986 fineness and 3.5 gm standard, including rare piedfort ducats (3-5 times the weight of a single ducat), minted with a lettered edge by Christoffel Adolphi in his private mint atelier.

Based on the work of L. W. A. Besier, total mintage (all mints) of gold ducats in the Netherlands between 1586 and 1808 was about 17.5 million pieces, of which the 18th-century strikes alone (1800-1808) consist of over 80% of this amount! The Holland mint minted about 53% of all gold ducats, meanwhile in Utrecht it was about 32%. Between 1586 and 1808 all other mints only minted about 15% of the total amount. Of these remaining mints the most numerous were those of Gelderland (approximately 6% of total amount) and West-Friesland (almost 4%). All Netherlands gold ducats minted after 1808 were struck in the Utrecht mint.

With the Ordinance dated March 17, 1694, all city mints (Deventer, Kampen and Zwolle) and also the provincial mints of Friesland were closed. Gold ducats were still being minted in the provincial mints of Gelderland, Holland, West Friesland, Utrecht and in smaller amounts also in Zeeland and Overijssel.

Even prior to introducing the Dutch type of a ducat in 1586, the Holland province stood strongly against minting debased coinage. After 1571 the Counts in the Low Countries (mostly in the Gelderland province area) “claimed” they minted gold ducats following the standards of either the German Empire or Gelderland, (in reality, the coins were debased). What they “claimed” depended on who was complaining about debased coins at the time: The Empire or Holland. So, when complaints came from Holland, they claimed to be minting under Empire law; and when the Empire complained they claimed to be minting under Gelderland law. Thus, neither entity could stop them from minting debased coins.

With the establishment of the Republic of Seven Provinces, the States of Holland wanted to limit the number of cities allowed to mint coins as much as possible. It was understandable, because profits from minting were considerable. Therefore, Holland stood against new West Friesland mints in the early years of the Republic. In 1673 they allowed the temporary Amsterdam mint to strike gold ducats, but only under condition that Amsterdam would stop minting immediately when it became possible to mint in Dordrecht again.

The Zeeland mint closed in 1799, and seven years later the mints of Gelderland, Holland, West Friesland and Overijssel stopped minting as well. Utrecht remained as the only facility allowed to mint coins. Although at first Amsterdam was chosen as a location for the new mint of the Kingdom of the Netherlands, in fact the mint stayed in Utrecht and exists there today. Since 1808, gold ducats–with minor changes made in 1817 (a slightly modified more modern design, the fineness lowered slightly from .986 to .983 and the weight lowered from 3.515 gm to 3.454 gm)–were minted in Utrecht.

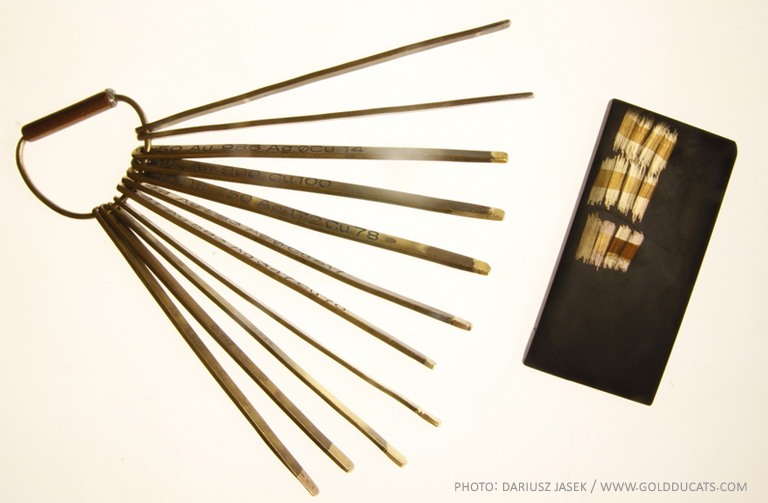

When speaking of the fineness of coins, we are usually thinking about a rough number given by the minting authority to be followed by the mintmaster; for example, .986 for gold ducats. But to measure the fineness isn’t easy, and certainly wasn’t easy back then. The testing of coins by the money changers required a lot of skills and special tools called karat needles and touch stones, which served this purpose for centuries and still do today. By comparing the color of scratches made by the coin being tested with the color of scratches made by karat needles (they were made of gold of a known fineness), they could estimate with remarkable accuracy the fineness of a coin. The same tools were used in the mint by the assayer.

There are usually between 13 and 16 karat needles in the set for testing gold, used by jewelers today. Each of them is made of gold of a certain fineness. Karat needles with the lowest fineness are made of gold and silver composition, those in the middle are made of gold, silver and copper in various ratios, and the highest fineness karat needle is made of gold with copper. A touch stone is a fine-grained and usually small black stone. In addition to observing the color of the mark that the tested objects made on the touch stone, the scratches are also treated with a testing liquid to see the color changes where the acid reacts with the marks on the touch stone. The testing liquid for testing a high-fineness gold (above 0.850) is made of 18 units of nitric acid and 24 units of hydrochloric acid, with six units of distilled water.

As we know from recent tests of gold ducats using modern equipment, the fineness of the Netherlands ducats measured was following the mint law well enough to call the practices of the mint assayers accurate. It is surprising, to most of us anyway, that a few centuries ago these masters could estimate the real fineness so well. On the other hand, these practices were completely unknown to ordinary people. They used to cut a coin or bite it to see if its core was indeed made of gold, or if the coin was merely gilded. What most people today don’t realize is that the practice of biting a coin to determine if it was genuine was not because gold is soft. To the contrary, they would bite the coin to make sure it was hard and not soft in the middle.

To make things worse, in the second half of the 18th century the number of counterfeited gold Netherlands ducats increased, and they were good enough to be found genuine by many. From the archive chronicles of Polish lands dated 1766 and 1768 we can read that the ability to distinguish counterfeit coins from the originals was only possible “after the close and difficult trials,” and this, in turn, “exposed a common man to a loss”, especially when coins were counted quickly in the transaction.

The karat needles and a touch stone being used by jewelers today. The third needle from the top has a fineness of 0.986. Inscription on the needle says: “50 Au 986 ø Cu 14” means “Needle no. 50, made of 98.6% of gold and 1.4% of copper”

The procedure of testing coins using a touch stone and karat needles in the jeweler’s workshop.

A touch stone with marks (scratches) made with different coins and with 0.986 gold karat needle.

The bottom line with five marks is made from – from the left to the right – two different Dutch gold ducats, a holed Utrecht 1608 ducat (fineness about 0.980), and a 19th century ducat (0.983 gold), – a Swiss 0.900 gold 20 Francs coin, and a Polish 2 grosze coin (not gold). The last one, the fifth mark, is made with a karat needle made of 0.986 gold.

* * *

Mr. Jasek’s recent book, Gold Ducats of the Netherlands, won the 2016 Numismatic Literary Guild (NLG) award for Best Specialized Book on World Coins. Be sure to visit his website at www.goldducats.com.

This is fantastic! Thank you Dariusz!