By David Thomason Alexander for CoinWeek …..

Selecting with absolute precision 10 of the greatest moments in the history of coin collecting in the United States is a daunting task. Numismatics has enjoyed more than 160 years of growth in the U.S. since its murky beginnings in the early 19th century. Its rollicking career has witnessed the struggles of pioneer collectors, endless hours of diligent labor by researchers and catalogers, lively controversies, booms and busts – all punctuated by sometimes incoherent intervention by local and national governments.

Through more than a century and a half of peace and war, prosperity and depression, Americans have sought out coins for their collections, contending with volatile coin markets, battered by contending waves of changing popularity of coin types and an ever-shifting base of interested collectors and dealers, hoarders and speculators. Bubbling in the background have been waves of inflation and day-to-day changes in precious metals values.

The years from 1857 to 2017 have witnessed an unending flow of change, accelerated since 1985 by the incoming tide of technology personified by third-party grading and the enclosure of coins in rigid plastic holders, otherwise known as “slabbing”.

Perhaps the first revolution in thinking needed to launch coin collecting was the acceptance of the idea that a coin could have a value not determined by its denomination. A cent could sell for a dollar or more, a concept that initially stuck in the craw of thrifty Americans to whom “a cent was a cent and a dollar was a dollar!” The cent was the ideal starter for new collectors, nearly all of whom could salt away a few without feeling guilty.

1.) The End of Large Cents and the Birth of Collecting: 1857

If a date could ever be chosen for the explosive beginning of popular coin collecting in America, May 25, 1857 would be a likely candidate. This was the launch date for the new Flying Eagle cent, a 19-millimeter, 4.67-gram coin composed of .88 copper and .12 nickel. The new copper-nickel coin replaced the 27.5mm, 10.8 gram pure copper large cent that had been struck by the Philadelphia Mint since 1793.

Such a change had been debated since the 1830s, when the cost of pure copper blanks had risen, hampering production of the large and inconvenient denomination that already was little loved by the general public, banking institutions and merchants. Neither the old cents nor their companion half cents were legal tender any longer, and both denominations could be (and often were) refused by disdainful merchants.

The unpopularity of the large cent had aided the circulation of Hard Times tokens a few years earlier. Early coin catalogers wrote that these tokens were created to counter a copper coin shortage, but this was not so. The tokens were issued by profit-seeking merchants who could obtain tokens for a few tenths of a cent each and wish them off on the public as a full cent. A cent from the U.S. Mint could not be obtained for less than face value.

The unpopularity of the large cent had aided the circulation of Hard Times tokens a few years earlier. Early coin catalogers wrote that these tokens were created to counter a copper coin shortage, but this was not so. The tokens were issued by profit-seeking merchants who could obtain tokens for a few tenths of a cent each and wish them off on the public as a full cent. A cent from the U.S. Mint could not be obtained for less than face value.

The Congressional bill authorizing the new cents passed on February 21, 1857, and was intended not only to retire older large cents and unpopular half cents but also to redeem quantities of worn foreign silver coins that had circulated for generations as legal tender at legally defined American values.

Most of these were Spanish or Spanish colonial pieces that were exhaustively cataloged in 1964 by Oscar G. Schilke and Raphael E. Solomon in America’s Foreign Coins (Coin & Currency Institute Inc., New York). This book was intended to increase collector interest in these historic coinages but failed to do so.

Redemption began on May 25, 1857 in the courtyard of the Philadelphia Mint, where a temporary building was built with two large payout windows: one labeled CENTS FOR CENTS, the other CENTS FOR SILVER. The scene on the morning of May 25 was recorded in detail in an upbeat report in the Philadelphia Bulletin noting the vast crowd that gathered to stand in line with bags, buckets, small boxes, even folded newspapers filled with old coins to be exchanged for canvas bags of glittering “nicks” as the new cents were nicknamed.

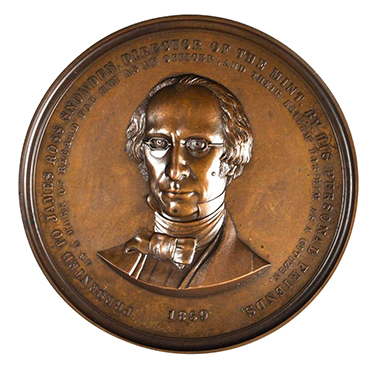

The line held a thousand coin-holders and slowly threaded its way through a long and tumultuous day. Mint Director James Ross Snowden estimated that three million new cents were handed out to these eager seekers. Most newspaper commentary was favorable to the new cent’s design, shape, metal and size.

Only after a couple of days did harsh criticism begin to emerge in the nation’s newspapers, panning the design, color and size of the new coins (though nobody expressed nostalgia for the disappearing cents or the worn silver). Too late was it realized that the old silver had been legal tender, and that the new cents were not. The disappearance of foreign silver left a gap not alleviated by the new coins. As months passed, criticism of the flying eagle design and of the new alloy grew shrill.

Only after a couple of days did harsh criticism begin to emerge in the nation’s newspapers, panning the design, color and size of the new coins (though nobody expressed nostalgia for the disappearing cents or the worn silver). Too late was it realized that the old silver had been legal tender, and that the new cents were not. The disappearance of foreign silver left a gap not alleviated by the new coins. As months passed, criticism of the flying eagle design and of the new alloy grew shrill.

This first use of nickel for American coinage was a bonanza for Philadelphia’s influential industrialist Joseph Wharton, who happened to own the only active nickel mine in the U.S. The new alloy proved exceedingly hard to work in the Mint, justifying its old German name Kupfernickel, meaning ”Devil’s copper”.

Another area boosted by the events of May 25 was coin collecting, then in its infancy in the U.S. There were probably no coin collectors anywhere in this bustling coin-exchange scene, though collecting ultimately received a massive boost from the disappearance of the familiar large cents.

2.) Collectors and Coin Markets

No one knows with certainty who America’s first coin collectors were.

In the early 1800s, learned gentlemen of leisure acquired a few ancient coins as adjuncts to Greek and Latin studies, or English coins illustrating their forebears’ lives under Henry VIII or Charles I. A very few wealthy families such as the Gilmors of Maryland had already begun to seek out rare U.S. coins, sometimes with the help of strategically placed friends on the U.S. Mint staff.

By 1857, pioneering coin collectors–such as Philadelphia’s Joseph J. Mickley (1799-1878)–realized that the large cent series was coming to an end and were trying to assemble date runs of the denomination out of circulation, seriously hampered by lack of knowledge of what dates actually existed for them to find.

By 1857, pioneering coin collectors–such as Philadelphia’s Joseph J. Mickley (1799-1878)–realized that the large cent series was coming to an end and were trying to assemble date runs of the denomination out of circulation, seriously hampered by lack of knowledge of what dates actually existed for them to find.

Many would spend years trying vainly to obtain a large cent dated 1815, arguing that since all other years seemed to be known, there must be an 1815 somewhere. The rarity of 1799 cents was highlighted when Mickley let it be known that he had searched for years for a cent from this, his birth year. All were “flying blind”, without accurate guides to what actually existed and could be collected.

Coin collecting and coin dealing began at essentially the same time. The earliest coin dealers tended to be gentlemanly sorts who also handled books, art works and other collectibles for well-to-do buyers. Edward Cogan of Philadelphia and later Brooklyn, New York came to be called “the English Daddy of the American Coin Trade.” Born in England in 1803, he came to Philadelphia at the somewhat advanced age of 50 to deal in books and paintings.

He shifted to coins in 1856 and held some of America’s first coin auctions before his retirement in 1879, publishing 70 catalogs that are sought by numismatic literature collectors today. After the Civil War, coin auctions expanded under such impresarios as Philadelphia’s Ebenezer Locke Mason and Captain John Haseltine, and Roxbury, Massachusetts’ lively William Eliot Woodward.

From New Jersey came the “Kindly Old Quaker Doctor” Edward Maris, a brilliant researcher-cataloger–especially in the large cent field and in the horse-head coppers of his native state. Fire and brimstone controversies were another highlight of this era, often launched in the house organs of such worthies as Swiss-born Edouard Frossard of Irvington-on-Hudson, New York. Virtually all established dealers joined in attacking the brash (and unforgivably successful) Chapman Brothers.

3.) Organizations Appear: 1857-1891

An early and logical step after collecting began was the banding together of collectors in clubs and societies. Such organizations were limited at first to a very few eastern cities, including Philadelphia, Boston, New Haven and New York. The earliest groups inherited the spirit of exclusivity or outright snobbishness then pervading existing historical societies.

The Boston society excluded more applicants than it accepted, including Lorin G. Parmelee, one of the earliest “mega collectors”, owner of an 1804 silver dollar and a Brasher doubloon. The reason? Parmelee was “in trade” (a wealthy Boston bean baker), and thus unfit for membership with such gentlemen as Jeremiah Colburn and Samuel Abbott Green. Philadelphia’s organization was just as exclusive and lapsed into inactivity after a few years.

New York proved an exception with the American Numismatic and Archaeological Society launched in 1857 by a small leadership core that included the youthful and energetic Isaac F. Wood. The Civil War interrupted the growth of this promising group, which beat the odds with its vigorous revival after the war, dropping “archaeological” from its title and becoming the ANS of today.

New York proved an exception with the American Numismatic and Archaeological Society launched in 1857 by a small leadership core that included the youthful and energetic Isaac F. Wood. The Civil War interrupted the growth of this promising group, which beat the odds with its vigorous revival after the war, dropping “archaeological” from its title and becoming the ANS of today.

The ANS grew into a giant of numismatic research, famed for its library and fast-growing collection of coins and medals. After years of wandering, the society settled into the classic building on upper Manhattan’s Audubon Terrace built through the generosity of benefactor Archer Milton Huntington.

Today, with its stellar record in numismatic research and publication, ANS ranks in the top echelon of numismatic organizations of the world.

This solid accomplishment had little significant effect on the growing population of general collectors in the U.S. in the late 19th century. These scattered collectors comprised what historian Dr. John Kleeberg has called the “small-town intelligentsia”: doctors, lawyers and clergymen of the South and the Middle West, most of whom lived far from the smattering of east coast societies.

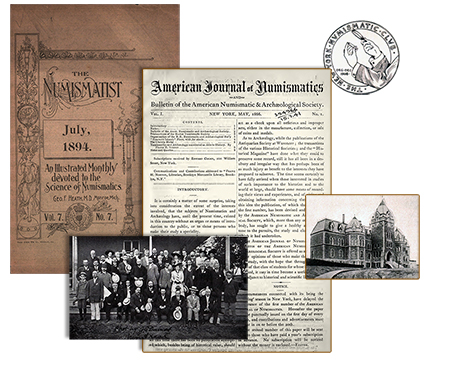

Perhaps a few of these received ANS publications such as The American Journal of Numismatics, but few were in a position to actively participate in the society’s ongoing activities. The answer to this situation was provided by Dr. George Francis Heath of Monroe, Michigan, who conceived a popular-level numismatic organization which would take the whole United States and Canada as its sphere.

A part-time coin dealer as well as a practicing physician, Heath began distributing a slim newsletter first called The American Numismatist in September 1888. Scattered short articles appeared amid the coin offerings in this infant publication, including “What’s the matter of having an American Numismatic Association?” in January 1888.

In March there appeared “A Plea for an American Numismatic Association”, quickly followed by the good doctor’s chosen slate for officers for the newborn organization. First president would not be Dr. Heath but William G. Jerrems of Chicago, Illinois. Other notables from the heartland and neighboring Canada including the dynamic Joseph Hooper.

As The Numismatist grew into a solid periodical, the new ANA slowly expanded while experiencing the growth pangs of all new organizations. Continuing efforts were made to secure active leaders for the organization, contributors to the journal, and attendees for the earliest conventions, most held in small Midwestern locales.

As with all other organizations, presidents of varying ability and leadership ability took office. Dr. Heath deferred to Jerrems; other early chief executives included poet, artist and writer Augustus G. Heaton, who proved ineffective and under whose faltering leadership the ANA nearly foundered.

The sequence of annual gatherings was broken so today’s conventions are properly called “Anniversary” rather than annual meetings. Heaton was far more successful as the author of one of U.S. numismatics’ most influential references, the 1893 Treatise on the Coinage of the United States Branch Mints, often called simply “Mint Marks”. This slim book forever riveted collecting U.S. coins by date and mint mark on future generations of collectors.

More able as ANA chief was Albert R. Frey of New York, a prolific writer and researcher and later a founder with Heaton and outspoken New York dealer Thomas L. Elder of the influential New York Numismatic Club (NYNC).

More able as ANA chief was Albert R. Frey of New York, a prolific writer and researcher and later a founder with Heaton and outspoken New York dealer Thomas L. Elder of the influential New York Numismatic Club (NYNC).

The hinterland really took control in the person of Pennsylvania native Farran Zerbe: an energetic, self-promoting figure whose overall demeanor suggested a carny grifter rather than a distinguished numismatist. After serving as ANA president, Zerbe continued directing the association through his hand-picked successor Dr. John M. Henderson of Ohio.

Zerbe became owner of The Numismatist in 1908, after Dr. Heath’s sudden death and used the “official organ” to further his personal feuds until 1910, when he sold it to Canadian member W.W.C. Wilson, who then presented the national organization with ownership of its own journal. From then on, The Numismatist was relatively free of political manipulation.

4.) New Coinages: 1878-1921

No later changes in the nation’s circulating coins generated the level of publicity that accompanied the great cent changeover of 1857. The long life of the Liberty Seated silver and Liberty head gold coins stifled collector interest in those series, and not even the surreptitious birth of the Morgan silver dollar in 1878 attracted substantial public interest at that time.

Revamping of the nation’s silver coinage, later the target of hysterical denunciation as the “Crime of 1873”, eliminated the silver dollar and silver three cents from the roster of circulating coins. No one in the East noticed or particularly cared at the time.

Mint Director Dr. Henry R. Linderman believed that a new silver dollar would become necessary, and went quietly overseas to hire a young English engraver, George T. Morgan, to come to the U.S. for the specific purpose of designing the new dollar. Linderman realized that his incumbent English engravers, William Barber and his son Charles, were uncooperative, slow-moving, untiring obstructionists and hoped to outflank them.

Morgan proved cooperative and of affable disposition; he worked hard, smiled and played cricket. After accepting the Philadelphia post, he endured 48 years of surly hostility from the unsmiling Charles Barber. Morgan’s silver dollar was adopted and struck in vast numbers from 1878 through 1904 and again in 1921. Few Americans ever got to spend or even see them, as most of the millions struck were consigned to dead storage as soon as made.

There was finally a brief flurry of interest in the redesigning of the nation’s silver coinage in 1892, when the Mint went through the motions of holding a design competition for a new dime, quarter and half dollar. A few artists took part, but they and their work were treated with vast disdain. In the end, Barber himself provided three dowdy designs.

In 1907 a different outcome followed serious wrangling between Barber on one hand, and the young and energetic President Theodore Roosevelt with his chosen sculptor Augustus Saint-Gaudens on the other. Saint-Gaudens was unarguably the greatest American sculptor of his day and had wrestled with Barber in 1892 over design of the participants’ medal of the World’s Columbian Exposition.

In 1907 Saint-Gaudens’ revolutionary designs for the gold double eagle and eagle ($20 and $10) were adopted, along with Bela Lyon Pratt’s incuse-relief Indian head designs for $5 and $2.50. These changes were truly historic, but involved coins that were realistically beyond the reach of most collectors.

In 1907 Saint-Gaudens’ revolutionary designs for the gold double eagle and eagle ($20 and $10) were adopted, along with Bela Lyon Pratt’s incuse-relief Indian head designs for $5 and $2.50. These changes were truly historic, but involved coins that were realistically beyond the reach of most collectors.

Vastly more accessible to them was the Lincoln cent adopted amid much publicity in 1909, designed by Russian-Jewish immigrant Victor David Brenner and generating controversy by first bearing his initials VDB. The Lincoln cent would become the “coin of entry” for millions of collectors in future years.

Nearly as popular was James Earle Fraser’s 1913 Indian head or buffalo nickel that became another piece of basic Americana. Silver coins adopted in 1916 as war clouds were gathering were Adolph Alexander Weinman’s triumphal Walking Liberty half dollar and Winged Liberty cap (“Mercury) dime and Hermon MacNeil’s Standing Liberty quarter. All of these coins could be obtained from circulation and had enormous effect on the spread of coin collecting.

5.) Books and Knowledge

As important as the coins themselves to collecting were objective reference books to guide the struggling collector. Until the 1930s, most available references were dealer publications: glorified price lists designed to sell coins, not to disseminate objective information. Indeed to a certain type of dealer, objective information and independent collector organizations were both to be avoided at all costs.

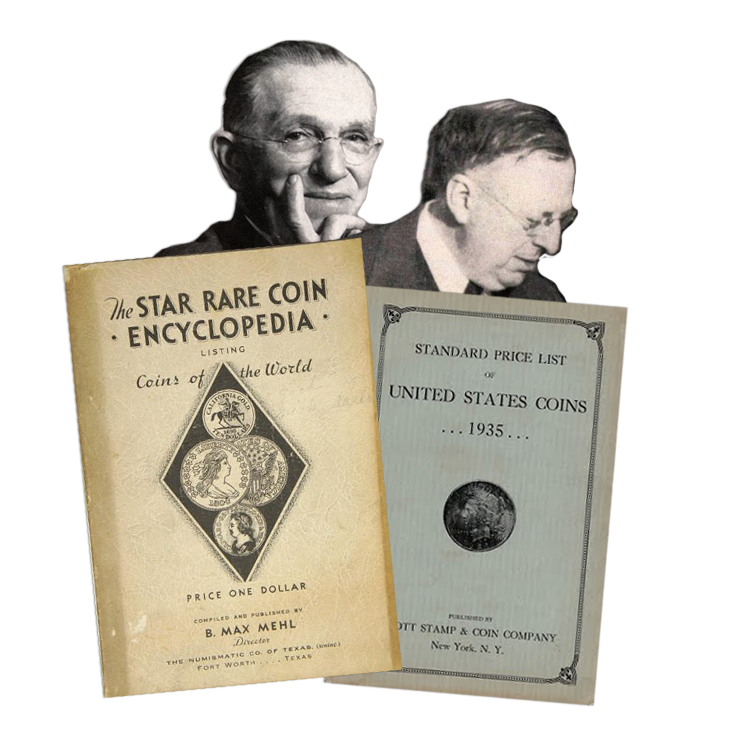

Some major dealers like B. Max Mehl of Fort Worth, Texas, (1884-1957) published such elaborate literature as his Star Rare Coin Encyclopedia along with auction catalogs. Many others offered price lists studded with misinformation to justify optimistic pricing. Old-line dealers including J.W. Scott (1845-1919) offered elaborate books with line-drawing illustrations.

Some major dealers like B. Max Mehl of Fort Worth, Texas, (1884-1957) published such elaborate literature as his Star Rare Coin Encyclopedia along with auction catalogs. Many others offered price lists studded with misinformation to justify optimistic pricing. Old-line dealers including J.W. Scott (1845-1919) offered elaborate books with line-drawing illustrations.

Wayte Raymond (1886-1956) was a coin dealing, auction and publishing phenomenon whose Standard Catalogue of United States Coins (later with tokens and paper money added to its content) provided factual information from 1934 to 1957. Raymond published a greater wealth of books, catalogs and guides through his long professional life than any of his contemporaries.

Raymond opposed fads in collecting, often deploring high market prices in volatile areas such as U.S. commemoratives, printing catalog values for such coins in italics as “speculative”. He distributed his books through what he described as “established coin dealers” rather than through more popular outlets.

A more dramatic and pervasive influence on the entire U.S. coin field has been wielded since 1947 by the Guide Book of United States Coins, known universally as the “Red Book”, the most widely distributed coin book in history. Although a heavy roster of numismatic greats have contributed to the annual editions for 70 years, a highly significant element in the book’s success has always been the matchless distribution network set up by Whitman Publishing.

Initially serving the needs of Whitman’s immensely popular Little Golden Books, this network also made possible nationwide distribution of the “Red Book”. Outlets included five-and-10-cent stores like Woolworth’s, and total availability spelled total success. This policy has been continued by the current publisher, Anderson Publishing of Atlanta, Georgia.

I will address five more of the greatest moments in American Numismatics in Part Two.

Great part one.

I’m interested in reading about the biggest mysteries in US coinage after recently reading about continental dollars. Any such recommendations? Thank you!