A Weekly CoinWeek Column by Greg Reynolds

News and Analysis regarding scarce coins, coin markets, and the coin collecting community #133 …..

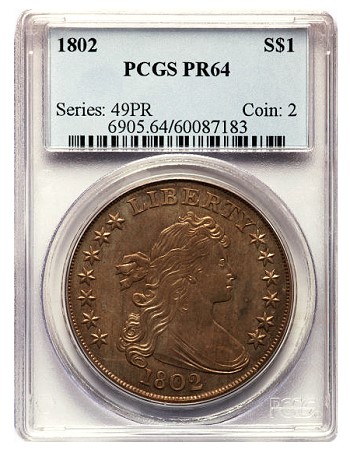

A Proof 1802 Draped Bust Silver Dollar is ‘in the news’ as it will be offered at auction by Heritage on Oct. 18th, as part of the “Greensboro Collection.” This 1802, which was earlier in the Jack Lee Collection, is held to be one of four “Proof”1802 dollars known to exist. Heritage is conducting the official auction of the autumn ANA Convention, in Dallas. I have found circumstantial evidence, far from conclusive, which suggests that there are five, rather than four, “Proof” 1802 dollars.

This Lee 1802 silver dollar is PCGS graded “64.” On Aug 3, 2012, Heritage sold another one, the Boyd-Cardinal coin, which is PCGS certified ‘Proof-65 Cameo.” In April 2008, the Carter-French-Queller 1802, also PCGS certified ‘Proof-65 Cameo,’ was auctioned. In 2001, the firm of Bowers & Merena (New Hampshire) auctioned the Dunham-Robison 1802, which probably remains PCGS certified Proof-64.

Martin Logies has extensively researched “Proof” 1802 Draped Bust Silver Dollars. Martin regards the Lee coin as “the third finest” of the four named, ahead of the Dunham-Robison 1802. Logies is the curator of the Cardinal Educational Foundation, which previously owned the “Proof” 1802 that Heritage auctioned on Aug. 3, 2012. Martin’s views regarding these are different from my own, and I am not implying that he is in agreement with the point that I am putting forth.

Herein, I discuss the status of the “Proof” 1801, 1802 and 1803 Draped Bust Silver Dollars. Furthermore, I question the prevailing wisdom that Proof 1802 dollars were struck in the 1870s. Moreover, I provide some evidence to suggest that the Lee 1802, which Heritage will auction this month, is not the Norweb 1802. If so, there exist five, not four, 1802 dollars. I raise issues relating to pedigree research, which apply to many rare coins, not just to “Proof” 1802 dollars.

I. Originals, Restrikes and Novodels

Of course, no Proof coins were minted in 1802. Furthermore, there were no special strikings of silver dollars in 1802. There is almost no chance that Proof U.S. coins of any denomination were minted prior to 1817, and early special strikings (“Specimens”), to the extent that these really exist, have characteristics that are much different from the 1801, 1802 and 1803 dollars that are widely regarded as “Proofs.”

The “Proof” silver dollars of 1801, 1802 and 1803 are often termed ‘novodels,’ rather than restrikes, as there are no original special strikings, Proofs or Specimens, of silver dollars of these dates. A coin that is made two or more years after the year (‘date’) that appears on it is often called a ‘restrike.’ When collectors think of restrikes, however, they often expect each ‘restrike’ to relate to a corresponding ‘original’ of a coin struck from the same (or very similar) dies that was made much earlier.

The “Proof” silver dollars of 1801, 1802 and 1803 are often termed ‘novodels,’ rather than restrikes, as there are no original special strikings, Proofs or Specimens, of silver dollars of these dates. A coin that is made two or more years after the year (‘date’) that appears on it is often called a ‘restrike.’ When collectors think of restrikes, however, they often expect each ‘restrike’ to relate to a corresponding ‘original’ of a coin struck from the same (or very similar) dies that was made much earlier.

Originals and restrikes exist of many Proof half cents from the 1840s. There are two categories of 1827 quarters, originals and restrikes, all Proofs. The originals were likely to have been struck in 1827, though might not have been. It is almost certain that the restrikes of 1827 quarters were struck many years later, perhaps decades later.

As the dies that were used to strike ‘original’ business strikes in 1801, 1802 and 1803, or thereabouts, are so different from the dies that were used to make “Proofs” of these dates after 1834, it is fair to conclude that the later pieces should be called ‘novodels,’ not restrikes. The term ‘novodel’ is often employed by collectors in Europe, and stems from Russian. If a pair of dies is very different from a corresponding original dies of the same date and type, and is used years after the ‘date’ indicated on the coins, then the ‘coins’ produced with the later pair of dies are novodels.

R. W. Julian points out that restrikes are novodels, too, according to the way the term is used in Russia. So, while all restrikes may be novodels, not all novodels are restrikes. “Proof” 1801, 1802, and 1803 dollars are best termed novodels and not restrikes, though calling them ‘restrikes’ is not harmful, in my view.

I put the term “Proof” in quotation marks in regards to these novodels, as their respective Proof characteristics tend to vary. Over the years, I have examined at least four 1803s, three 1802s, and an 1801. It is not clear that all meet sufficient criteria to be termed Proofs, in terms of detail, depth of field, relief of devices, etc. It is clear, however, that these are not business strikes. Indisputably, they are special strikings from heavily polished dies. So, referring to them all as “Proofs” is fair enough, as they have all been called “Proof” for well over a century. It may be counterproductive to refer some as being ‘more Proof’ than others.

I put the term “Proof” in quotation marks in regards to these novodels, as their respective Proof characteristics tend to vary. Over the years, I have examined at least four 1803s, three 1802s, and an 1801. It is not clear that all meet sufficient criteria to be termed Proofs, in terms of detail, depth of field, relief of devices, etc. It is clear, however, that these are not business strikes. Indisputably, they are special strikings from heavily polished dies. So, referring to them all as “Proofs” is fair enough, as they have all been called “Proof” for well over a century. It may be counterproductive to refer some as being ‘more Proof’ than others.

II. Were 1802 dollars struck in the 1870s?

The borders, outer devices, edge characteristics, and other structural factors relating to Proof 1802 Draped Bust Silver Dollars demonstrate that these are issues that are very different from the business strike 1802 dollars of the ‘same’ Draped Bust obverse (front), Heraldic Eagle reverse (back) design. The technology used to strike them is clearly different, and the style of the outer devices is different in some respects, especially the borders at the rims.

In a book that was published in the early 1960s, Eric Newman and Kenneth Bressett put forth a strong case that the Proof silver dollars of 1801, 1802 and 1803 and the ‘Class I’ silver dollars of 1804 were all struck with the same reverse (tail) die. Historical documents indicate that ‘Class I’ 1804 silver dollars, so called ‘originals,’ could not have been struck before 1834.

In my view, it is likely that all eight known ‘Class I’ 1804 silver dollars were struck during the 1834 to 1835 period. There is widescale agreement among researchers that the lone ‘Class II’ 1804 and six ‘Class III’ 1804 dollars were minted in 1858 and/or later. Newman & Bressett discovered that the ‘Class I’ 1804 dollars were struck from a reverse die, which they term ‘X,’ different from the reverse die that they term ‘Y’, which was used to strike the Class II and Class III 1804 dollars.

Newman & Bressett further discovered that the Proof Draped Bust Silver Dollars that are dated 1801, 1802 and 1803 were struck with reverse die ‘X,’ which was used to strike “original,” but not “restrike” (later made) 1804 dollars. If the Proofs of 1801 to 1803 were really made after 1858, it would seem more likely that they would have been struck with reverse die ‘Y,’ like the Class II and Class III 1804s, which almost certainly were made in 1858 and/or later.

Q. David Bowers (QDB), John Dannreuther(JD), and various Heritage cataloguers suggest that the Proof 1801, 1802 and 1803 dollars were struck in the 1870s. In my view, the evidence is not convincing and it is a little misleading to suggest that these novodels were made in the 1870s. These could have been struck at various times between 1836 and 1870.

Arguments supporting a minting date in the 1870s tend to fall into five categories:

- (1) Proof 1801, 1802 and 1803 dollars were not publicly offered until the 1870s.

- (2) None of the known pieces circulated and most of them now grade 64 or higher.

- (3) The evidence of rust on reverse die ‘X’ suggests that the 1801, 1802 and 1803 novodels were made later than 1835 and not all in the same time period.

- (4) QDB and also JD have argued that the “striking quality” of these suggest that they were made in the 1870s.

- (5) They were struck on planchets (prepared silver blanks) that were heavier than those used for business strike silver dollars dating from before 1873 and were within legal “tolerances” for Trade Dollars, heavy silver coins that were minted for international trade in the 1870s.

I address these arguments one at a time.

(1) Proof 1801, 1802 and 1803 dollars were not publicly offered until 1876. So what, there are many rarities that reside in family collections for decades. For example, a father/son collecting team bought many coins at the auction of the Eliasberg gold coins in Oct. 1982 and still have them, thirty years later. Moreover, if a U.S. Mint employee or a well connected collector took possession of some Proof Draped Bust Dollars at some point between 1835 and 1860, it would not be surprising that these were not publicly offered. One collector, possibly a former U.S. Mint employee, could have kept them for decades.

If someone inherited ten to twenty Proof silver dollars from a wealthy collector or from a U.S. Mint official , these might have just sat in a bank vault or family safe for decades. Most non-collectors would not even realize that these were worth much over face value, which would hardly be a vast fortune. It is extremely plausible that a collector, a heir to a collector, or a family, might have owned, for decades, a dozen or more Proof silver dollars?

Besides, the members of a family that currently owns the Walton 1913 Liberty Nickel do not seem to be in any hurry to sell it. They, surely, are aware that it is worth some amount between $2 million and $4 million.

It may be relevant that employees of the U.S. Mint in the 19th century were often related ‘by blood’ or via marriage to other U.S. Mint employees. Indeed, the Philadelphia Mint was an environment characterized by nepotism, meaning that relatives of employees had strong advantages over non-relatives when applying for jobs or being considered for promotions. A relevant point here is that a Philadelphia Mint official in the 1870s could have inherited some of all of these from someone else at the Mint, who made them in the 1830s or 1850s. A realistic possibility one U.S. Mint official could have sold Proof silver dollars, while acting as an agent for another who was retired or elderly.

Also, an 1885 Trade Dollar was not publicly displayed until 1908. It does not follow from this fact that it was made after 1900. For reasons that I will discuss in the future, it is very likely that all 1885 Trade Dollars were actually struck in 1885 or in Dec. 1884.

The unique 1870-S half dime did not appear publicly until the 1970s, more than a century later after its ‘date.’ Yet, it is likely that it was minted in 1870.

(2) None of the known novodels circulated and most of them now grade 64 or higher. Who would expect Proof Bust Dollars to circulate? Furthermore, there are numerous Proof coins dating from the 1830s or 1840s that now grade 64 or higher. If the Proof 1801 to 1803 Proof silver dollars had one owner for decades, prior to the 1870s, it would then be unsurprising that most of them would be gem quality coins.

Enough gem quality, U.S. coins from 1793 to the 1840s survive now to demonstrate that there were collectors and other owners during the first half of the 19th century who properly cared for their respective coins. Additionally, there could have been additional Proof 1801, 1802 and 1803 dollars that were lost over time.

In the 19th century, it was not unusual for coins and other valuables to be damaged in fires. Damaged silver coins were probably melted.

(3) The evidence of rust on Reverse ‘X’ suggests that these were made later than 1835 and not all in the same time period. The amount of rust on a die is largely a consequence of how it is stored rather than the passing of time, though, of course, some time is needed for rust to occur. For storage, a die was ‘greased,’ waxed, or otherwise treated to limit rust.

A die that was not prepared for storage and was kept in a particularly humid area, perhaps near a drainpipe or a sink, would rust fast, in a matter of months. The climate is humid in Philadelphia and this city is not far from the Atlantic Ocean, which contains salt water. There was not air conditioning, as people now know it, in the middle of the 19th century. In theory, the rust on Reverse ‘X’ could have occurred in a matter of months.

(4) As for the notion that the “striking quality” of these suggest that they were made in the 1870s, this argument is peculiar and is inconsistent with the history of Proof U.S. coins. For Proof U.S. silver coins, the 1870s constituted a ‘dark age.’

Proofs of the 1840s, the 1860s and the 1890s all, on average, had much stronger Proof characteristics than the Proof U.S. silver coins of the 1870s, which were often mediocre or very weak. If a Proof U.S. silver coin, with a mysterious date, has powerful Proof characteristics, then this would be a reason to believe that it was NOT struck in the 1870s.

(5) Proof 1801, 1802 and 1803 dollars tend to weigh around 420 grains (seven-eighths of a Troy ounce), the weight standard for Trade Dollars. There were legally acceptable deviations, “tolerance.” In another words, it was legal to strike coins for circulation on planchets (prepared blanks) that weighed a little more or a little less than the standard. The range of allowed deviation from the standard is called a “tolerance.”

On Jan. 18, 1837, the weight standard for silver dollars was decreased from 416 grains to 412.5 grains (about 0.859 Troy ounce). Although variations in weight may be puzzling now, the reality is that weights of silver coins varied. One reason for a legally allowable “tolerance” is that planchets (prepared blanks) tended to vary considerably. Large numbers of planchets were melted because their weights failed to fall into the allowed range, within the “tolerance.”

In my view, it is incorrect for QDB to assert that, “prior to 1873, the Mint would not have had planchets weighing 420+/- grains on hand.” There would have been plenty of them at various times between 1836 and 1870.

R. W. Julian asserts, in a conversation on Oct. 8th, that, “in all time periods, there were many planchets that were overweight and out of tolerance. These would be lying around until they were melted.”

Importantly, before 1854 or so, the bureaucratic procedures relating to Proof coins were similar to those for medals. In the Jan. 9, 2009 issue of Numismatic News newspaper, R. W. Julian emphasizes that “Proofs for collectors” were “not subject to legal tolerances” regarding weight. Moreover, Julian makes clear that “a dollar planchet” weighing significantly more than the then current standard “could not be used for circulating coinage but was available for Proof coinage.” In general, it was legal to use heavy planchets, out of tolerance, for Proof coins.

Indeed, in response to my questions, Julian explains that, “for clandestine strikings, it would have been much easier for record-keeping purposes to use planchets that were [way] overweight, out of tolerance, than it would have been to use planchets of [proper] weight at the time because the [proper] planchets had to be accounted for, while the [way] overweight planchets were just simply re-melted,” R. W. Julian remarks.

Julian stresses that way “overweight planchets, out of tolerance,” were listed as “clippings” or as excess silver bullion, and could easily be replaced with the same amount of silver. In effect, silver bullion could easily and quickly be traded for way overweight planchets. So, it is likely that “overweight, out of tolerance, planchets,” would have been used to strike the Proofs of 1801, 1802 and 1803. The fact that the planchets used were within weight tolerance for Trade Dollars, which were first struck in 1873, is a reason to believe that these novodels were made long before 1873.

In another words, all Trade Dollar planchets, with legal weights, within tolerance, “had to be accounted for,” and thus it is unlikely that those making clandestine strikings” would use them, because paperwork would be required, Julian concludes. It would be much easier, for clandestine strikings and sometimes for patterns, to use planchets with weights that were “out of tolerance.”

Also, Julian contends that all coins and patterns struck in the 1870s would have been dated in the 1870s. “Sure,” there were “clandestine strikings in the 1870s, but these had dates in the 1870s. Henry Linderman [who was in charge] had a lot of coins and patterns struck for his purposes, but no pieces with early dates,” in Julian’s view.

III. Are the Lee and Norweb 1802s the Same?

There is no doubt that the Proof 1802 dollar that Heritage will auction on Oct. 18th is the exact same coin that Heritage sold in Nov. 2005, when it was then part of the Jack Lee Collection. As the late Jack Lee is a legendary collector of silver dollars, it makes sense to refer to it as the Lee Proof 1802.

Several researchers who have considered Proof 1802 dollars have accepted the notion that the Lee 1802 is the same as Norweb 1802, which was auctioned by Bowers & Merena in the Norweb III sale of Nov. 1988, in New York City. Some depressions on the Norweb coin exactly match corresponding depressions on the Lee coin.

Several researchers believe that these depressions (indentations) are flaws in the planchet. I maintain, however, that these depressions stem from the die, not the planchet. A pair of dies, obverse (front) and reverse (back), is used to strike the devices (design elements and borders) on to a prepared blank (planchet) to produce a coin.

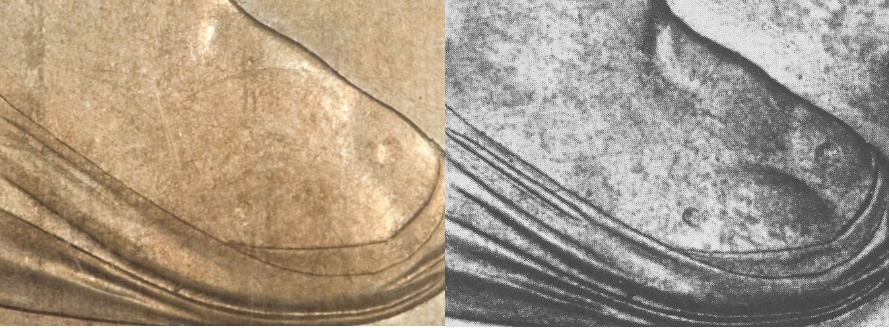

Plus, if the pictures in the Norweb III catalogue are fair enough, there are differences between the depressions on the Lee coin and those on the Norweb coin. For example, the depression at the border near star number 10 and star #11 seems to be deeper on the Norweb piece than on the Lee piece. Other depressions seem to be shallower on the Lee piece as well.

Overall, my analysis of pictures and images suggest that the Lee 1802 was not struck with as much force and/or not as many times as the Norweb piece. In several areas, the Lee piece seems to have considerably less detail than the Norweb piece.

I note the hair curls above Miss Liberty’s forehead, and also the bottom portion of her hair. Other areas of her hair should be scrutinized as well, especially near the ear. Clearly, the large picture of the obverse of the Norweb 1802 in the Norweb III catalogue, when compared to the excellent images on HA.com, give the impression that the hair of Miss Liberty on the Norweb 1802 is much more sharply struck than the corresponding hair on the Lee 1802.

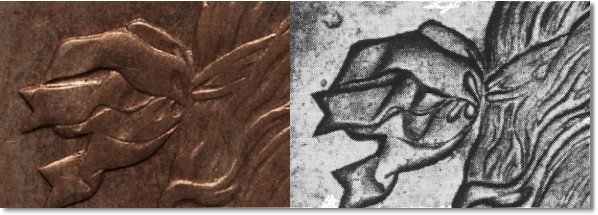

Although the large picture of the reverse of the Norweb 1802 is not as clear as that of the obverse in the B&M catalogue of Nov. 1988, it appears that the tail feathers of the eagle are sharper on the Norweb 1802 than on the Lee 1802. Moreover, there is an indentation on the leftmost cloud on the Lee 1802, due to a thread or wire on the die, which does not seem to be present in the catalogue pictures of the reverse of the Norweb 1802.

Could the catalogue pictures of the Norweb 1802 have been badly processed or be misleading for other reasons? I do not know. The staff at Bowers & Merena in 1988 was generally regarded as honest and sensitive to pedigree research. I find it hard to imagine that the pictures were doctored or carelessly transformed.

Is it possible that the PCGS holder housing the Lee 1802 is scuffed or clouded such that pictures of the coin in the holder suggest that Miss Liberty has less detail than she does in actuality on the Lee 1802? I saw this coin in Philadelphia in Aug. 2012 and I do not remember marks on the holder lessening my ability to examine the Lee 1802. It is impossible to account for all the variables that may affect photography and the accuracy of published images, however, and some detail on the coin will not be apparent in images.

My honest impression is that the pictures on HA.com of the Lee 1802, dating from 2005 and from 2012, are very clear and that the pictures in the Norweb catalogue are clear enough to make a strong case that the Norweb 1802 has substantially more detail and is not the same as the Lee 1802. Although I am not certain about the Norweb 1802 and the Lee 1802, there are issues relating to catalogue pictures and pedigree research that should be discussed, including notions relating to die caused imperfections on coins.

IV. Depressions on Coins

I prefer to refer to depressions on coins as indentations, though I will use the term ‘depression’ here as many people are not accustomed to using the term ‘indentation.’ The term ‘depression’ has a negative connotation in general and, in regard to coins, it is not clear. The term indentation is neutral and refers to relevant planchet flaws, die caused defects and contact marks of significant size, all of which are ‘below’ the levels of the affected fields and/or devices (raised parts).

The Norweb and Lee 1802 dollars are characterized by a few somewhat circular, slightly bowl shaped forms. These seem sunken.

I maintain that these depressions are caused by unusual matter on the obverse (front) die. An object on a die typically causes a depression (indentation) on a coin that is struck with that die. There is a category of planchet flaws, often due to trapped gases or contaminating trace metals, where pieces of metal (planchet flakes) fall off, leaving depressions. The depressions caused by such planchet flaws, however, are ‘rough inside’ and/or are characterized by textures of metal inside that are much different from the surrounding metal on the coin. The depressions on the Lee 1802 are smooth inside and are largely consistent, in texture and color, with the surrounding metal.

During much of the 19th century, there were no electric vacuum cleaners at the Philadelphia Mint. It is known that there were issues with the dies used to make these novodels and 1804 dollars. There were chips, die cracks and die rust. As for the materials used to polish and treat dies in the 19th century, little is now known by researchers.

It stands to reason that dies for 1802 dollars were treated differently from dies in routine settings. These dies were improperly stored. These were probably in need of treatment and/or ‘conservation’ themselves. I suggest that, somehow or another, small pieces of metal, some perhaps with dark ‘goo’ on them, dark chemical compounds, trace metals and/or other matter was present on the dies used to strike Proof 1802 dollars.

If the Norweb and Lee coins are the same coin, then the fairly large depressions may only be found on it. If these are different coins, then these may be the only two novodels characterized by fairly large depressions.

Either way, there is an obvious explanation. The medium sized pieces of metal that were responsible for such depressions clung to the die via static electricity or by way of some substance used to polish or treat the die, perhaps some ‘goo.’ The operator of the coining press just wiped off these pieces of metal, so subsequent strikings, if any, of 1802 dollars would not also have such depressions.

In the 19th century, it was not unusual to wipe, treat or further polish dies between strikings of Proofs. So, it would have been routine to remove the pieces of metal (or other fabric) adhering to the dies that lead to or may lead to depressions on struck coins. I am convinced, however, that were additional substances on the dies that caused small dark ‘spots,’ possibly including extremely shallow, additional depressions.

V. Dark Spots

There are similar dark spots on all known 1802 dollars. As the Boyd-Cardinal (PCGS Pr-65 Cameo) and Dunham-Robison (probably PCGS Pr-64) were dipped within the last thirty years, many of these spots were partly or fully dissolved by the acid in the dipping solutions. In some areas, remnants of dark spots can be seen. Moreover, there is agreement among experts that the Carter-French-Queller (PCGS Pr-65 Cameo) 1802 was ‘conserved’ between Jan. 1989 and April 2008, as it later had less toning and fewer spots than it had in 1989. I am not commenting here as to whether such conservation was harmful. Opinions relating to conservation are beside the points of the present discussion.

I am convinced that there are some dark spots that are present (or were present) on two or three different 1802 dollars in the same locations or in locations that are close to being the same. The inescapable conclusion regarding these dark spots is that they were brought about by substances on the dies, which could be just one chemical or a combination of substances. There could have been polishing fluids, cleaning fluids, accidentally spilled lubricants, stuff falling off the hands or gloves of a coining press operator, or other sources for ‘stuff’ on the dies.

There could have been just one thing, or, more likely, a combination that accounted for some of the dark spots that are found (or were found) on multiple 1802 dollars. An examination of these coins with a suitable microscope would indicate that the dark spots were accompanied by slight depressions. In another words, there was stuff on the dies that caused dark spots on the coins.

This relates to pedigree research as dark spots that seem to identify a coin may really stem from a die, and not be unique to a specific coin. Other spots, however, truly are just toning and do not relate to my point here.

Consider a dark spot between the E and the S of STATES. I see it on the catalogue image of the obverse of the Dunham-Robison 1802 in the catalogue of the B&M sale of the Flanagan Collection in 2001. I strongly believe that I see the same spot in the pictures of Proof 1802 dollars in the Norweb (11/88) and French (01/89) catalogues, respectively. The Carter-French-Queller 1802 was auctioned by Stack’s on Jan. 18, 1989. A spot in the same location is on three different 1802 dollars.

If a dark spot was caused by a chemical soaked piece of fabric, or a piece of black gel on the die, it could move around, and thus appear on slightly different locations on different coins struck from the same obverse die. While this sounds weird, it was not unusual, in the 19th century, for a piece of foreign matter on a die to move around and thus be in slightly different locations on different coins struck from the same die.

Lint or pieces of cloth on dies used to strike Proof gold coins and Proof Indian Cents are examples. Indentations from the same thread or piece of fabric on the same die may be found in different locations on different gold coins that were struck with the same die.

I see a dark spot above the bow in the field in the large catalogue picture of the obverse of the Norweb 1802. Moreover, there is a very similar spot, in terms of location and size, on the Boyd-Cardinal 1802 that Heritage sold on Aug. 4th, in Philadelphia. In the color picture of the obverse of the Carter-French 1802, in the Stack’s catalogue of Jan. 1989, there is a very similar spot. In one of the Heritage images online, relating to the April 2008 auction of the Carter-French-Queller 1802, this spot is almost visible, a trace of it remains.

In sum, I am convinced that some of the dark spots on 1802 dollars stem from the dies. Other dark spots are due to toning or carbon. There are many variables that may affect the surface characteristics of a coin.

VI. Was the Norweb 1802 Dipped?

Researchers who contend that the Norweb 1802 and the Lee 1802 are the same coin must be asserting that the Norweb 1802 was dipped after it was auctioned in Nov. 1988. After all, it then had much green and blue toning.

When the Lee 1802 was offered at auction in Nov. 2005, it was a nearly uniform gray color as it was when I saw it August in Philadelphia at the Heritage table at the ANA Convention. It may have been slightly darker in 2012.

If the Lee 1802 is the Norweb piece, it was dipped and has naturally retoned in the interim. In my view, the Lee 1802 does not have the ‘look’ of a coin that has been dipped over the last eight years. Could it have been dipped in the 1990s? I cannot now say.

I saw the Norweb piece, long ago. While I do not have a crystal clear recollection of it, I noted that it had very attractive green and blue toning. The cataloguer in 1988 graded it as “65,” during an era when grading standards were stricter than they are now. Moreover, many coins from the Norweb Collection were, even in the 1980s, certified by the PCGS and the NGC with grades that were higher than the catalogue grades for the same coins, sometimes much higher. A Norweb coin that was catalogued as grading 65 or 66, in numerous cases, was certified as grading 67 or 68.

The Lee 1802 has been PCGS graded 64, at least since Nov. 2005. It is unlikely that it will upgrade in the near future. The 64 grade seems right.

If the Norweb coin became the Lee coin, and was dipped at some point along the way, someone may have taken a substantial financial loss, even though prices for Proof 1802 dollars have climbed to a great extent over the years. Circumstantial evidence suggests that the possibility that the Norweb Proof 1802 would have been PCGS or NGC graded 65 or 66, possibly even 67, in which case, it would be worth much more than the Lee coin is worth now.

Usually, when a very expensive coin is dipped, it is done by an expert wholesaler who calculates that it would receive a higher grade after being dipped than it would otherwise. Very expensive coins that are very darkly toned, often with black or deep brown areas, are candidates for dipping by profit-seeking wholesalers.

While it is possible, is it likely that an expert wholesaler would have regarded the Norweb 1802 as a candidate for dipping? A certified Proof-65 or -66 1802 is worth much more than a certified Proof-64 1802. Sure, it is possible that the grade would have been higher after attractive green and blue toning is removed, but would dipping the 1802 have involved a rational risk, from a financial standpoint?

Perhaps, from a profit-mongering perspective, a dealer would have had more to lose than to gain by dipping the Norweb 1802! This is still another reason to suggest that the Norweb 1802 and the Lee 1802 are different coins. There probably was not a rational, financial reason to dip the Norweb 1802 and, if it was not dipped, the Lee 1802 is necessarily a different coin. Even if the Norweb 1802 was dipped, the Lee 1802 might still be a different coin.

Further research may shed light upon the pedigrees and condition rankings of Proof 1802 and of Proof 1803 silver dollars. I am skeptical of the currently accepted pedigree listings.

©2012 Greg Reynolds

First Addendum: Rebuttal of Counterpoints by David Stone and P. Scott Rubin

Oct. 18, 2012

Counter-Point #1) David Stone remarks, “There would have to be A LOT of foreign objects sticking to the hammer die to recreate all those depressions on two different coins.”

1A) Yes, there were “A LOT of foreign objects” on the obverse die, when the Norweb 1802 and the Lee 1802 were struck. I have seen other Proof silver coins and Proof gold coins that were struck with a significant number of such objects, though not quite as many.

1B) Since writing the above article, I have come across remarks by Q. David Bowers and by researcher Breen in regard to Proof 1858 quarters. Many of these also have a large number of depressions and other indentations from foreign matter adhering to the obverse (front) die. I will write about Proof 1858 quarters, perhaps next week.

P. Scott Rubin: “I do not think we will ever find proof of when they were really made because the people who made them did not want to be discovered.”

1C) I agree that “Proof” 1802 dollars were made secretly. So, these are more likely to be characterized by U.S. Mint caused imperfections than other mid 19th century Proof coins, for three reasons relating to secrecy. First, it is likely that just two or three people were involved and that they were in a hurry. They did wish to be noticed, even by a janitor or a security guard, while making unusual pieces for personal purposes. Second, these could have been struck late at night and in a room that was mostly dark. Third, “Proofs” struck in this manner would not have been subject to formal or informal quality control reviews.

1D) In other circumstances,“Proof” coins that have so many depressions and other indentations would have been sent to a different room to be melted. Someone who was making “Proof” 1802 dollars (after 1834) for his own collection, without authorization, would not have done the paperwork to have problematic pieces melted and to requisition replacement planchets. They probably had to wait for an opportunity to take suitable planchets, which were rejected as overweight, which would otherwise have been melted, anyway.

The fact that these were made secretly is the main reason why sub-par “Proofs” would not have been melted. If openly produced, regular Proof coins had so many depressions and other indentations, then these would typically have been rejected and set aside to be melted.

Counter-Point #2) Stone: “There are also a few marks, like the one P. Scott Rubin mentions in Liberty’s hair, that are plainly contact marks, not planchet flaws or die anomalies.”

No, these are also due to foreign matter on the obverse (front) die.

2A) The fact that there is a lot of foreign matter on the die fields demonstrates that some was likely to have gotten into the recessed areas of the dies, which produce the raised design elements on the struck coins. The dies were probably wiped with something that was thought to have been ‘clean,’ yet had a large number of sticky particles, of metal or fabric.

2B) Upon magnification, it becomes apparent that the “scratches” identified by Stone and by P. Scott Rubin are not scratches at all. Some of the same kinds of indentations that are present on the fields are in the hair, too. As I said in the main body of the article, there appears to be an indentation in one of the clouds on the reverse (back) of the Lee coin that is not present on the Norweb coin. I am certain that there are many indentations on the design elements, including Miss Liberty’s hair, that are from the dies. In some of these cases, there are just very small indentations that may seem to be contact marks at first glance.

2C) I saw the Lee 1802 in Philadelphia. There were no significant scratches in the hair. The cataloguer in 1988 graded the Norweb 1802 as “65.” In 1988, a noteworthy Proof coin that had noticeable scratches in the hair would not have had a chance of receiving a “65” grade. Besides, as I mentioned, many of the coins in the Norweb III sale were undergraded by the cataloguers, in terms of the grades assigned soon afterwards by the PCGS or the NGC. Circumstantial evidence suggests that the Norweb 1802 is a much higher quality coin than the Lee 1802.

2D) Assuming that the pictures published in 1988 are honest, the Norweb 1802 is certainly more sharply struck than the Lee 1802. The dual image below should serve as a comparison of the area where some say that there is a common “scratch” or two. I do not remember seeing any such scratches and none are evident in these images. Some indentations are found on both coins because of small particles on the die.

Counter-Point #3) Stone: “The coin was undoubtedly conserved at some point between its appearance in the Norweb sale and the Jack Lee catalog. Remember the magnificent toned 1893-S Morgan dollar in lot 3887 of the Norweb sale. It also became part of Jack Lee’s collection.”

This comment by Stone is misleading.

3A) I am the one who educated the coin collecting community about the conservation of the Norweb 1893-S. Please click to read the relevant article.

3B) The Norweb 1893-S dollar was ‘conserved’ at the request of a collector/speculator who owned it AFTER Jack Lee owned it.

3C) The Norweb 1893-S was naturally toned russet and gray. The Norweb 1802 is (or was) naturally toned shades of blue and green.

3D) The Norweb 1893-S does not (or did not) have any particularly noticeable imperfections, U.S. Mint caused or otherwise. The Norweb 1802 and the Lee 1802 both have many U.S. Mint caused imperfections, the depressions and other indentations. These would ‘stand out’ immensely if a coin was dipped. As I said in the main article, it is possible, though unlikely, that the Norweb 1802 was ever dipped.

3E) It is much more likely that a Morgan Silver Dollar will be assigned a higher grade by the PCGS or the NGC after being dipped than a Draped Bust Silver Dollar will be after being dipped. Different grading criteria are used for these two types. Bright white Morgans are encountered all the time; it is very unusual to see a bright white, Draped Bust Silver Dollar.

4) Stone says, “the other differences you see in the photographs are due to light, shadow, and picture quality, which can cause the same coin to appear much different under different conditions.”

4a) The Norweb 1802 has MUCH more detail in the hair and experts at Heritage took four (4) sets of images of the Lee 1802, two in 2005 and two in 2012. If there was anywhere near as much detail in the hair of the Lee 1802, it would have appeared in the sharp, high resolution images done by Heritage. There are many additional strands of hair, and better developed strands of hair, plus other additional details, in the picture in the Norweb III catalogue than in any of the four Heritage pictures of the obverse of the Lee 1802 .

The additional detail in the picture of the Norweb 1802 cannot be due to lighting. Clearly, the hair on the Lee 1802 is not sharply struck, and Miss Liberty’s hair on the Norweb 1802 is sharply struck.

4b) I examined the Lee 1802 in Philadelphia in August 2012. The hair of Miss Liberty is weakly struck. There is no doubt about it. It is not a question of cameras and scanners at Heritage failing to capture detail present. There is much less detail on the Lee 1802 than on the picture of the Norweb 1802.

While it is theoretically possible that an obverse image of the Norweb 1802 could have been extensively reworked by people at Bowers & Merena (New Hampshire) in 1988, my guess is that this is unlikely. First, a skilled graphics artist would probably have to had, in 1988, access to a detailed picture of another Proof 1802 or a Proof 1803 dollar, to know what detail to add, and, even then, the process would take many hours. Second, I know (or knew) several of the people who were employed by Bowers & Merena in 1988, and I really do not believe that the staff at this firm would have extensively doctored the obverse picture of the Norweb 1802 . I admit, though, that I have never been knowledgeable about the production process for the catalogue of the Norweb III sale.

Note that the chest and neck are better defined on the Norweb 1802 than on the Lee 1802:

Second Addendum: Indentations Confused with Scratches, response to Rubin

Oct. 24, 2012

I welcome challenges to the positions put forth in my articles and columns. Indeed, I am delighted when prominent coin enthusiasts, like Scott Rubin, wish to argue points. I admit that I should have more clearly stated that foreign matter on dies does not just adhere to the fields; foreign matter may adhere to the devices (design elements) as well and did in the case of the Lee 1802 silver dollar.

In the main body of the above article and in the first addendum, I draw attention to the fact that there was much foreign matter on the dies and I emphasized that it was not unusual for Philadelphia Mint personnel to wipe, treat and/or further polish dies between strikings of coins intended to be Proofs. So, it would have been routine to remove the pieces of metal (or other fabric) adhering to the dies that caused or may lead to depressions or other indentations on struck coins. Therefore, it was not unusual for one pair of dies to be used to strike coins that have depressions and other indentations and then be used to strike additional coins that do not have such indentations.

As for why it seems that at least two Proof 1802 dollars were struck with so much foreign matter on the dies, four points come to my mind. 1) These were probably struck in a hurry. 2) Because of the very secretive nature of this mintage, coins intended to be Proof 1802 dollars may have been struck late at night and/or under very poor lighting conditions. 3) As I indicated in my first addendum, the people making these probably were not able to send sub-par pieces to be melted and produce replacements, as was often done, in ordinary circumstances, when coins intended to be Proofs were defective. 4) In the near future, I will provide examples of other 19th century U.S. coins that were struck with considerable foreign matter on the dies.

P. Scott Rubin further comments, “…what you do not seem to understand is that the mark near the curl is not on any of the other three 1802 [novodels.] … There is another such mark in the hair that appears on only this coin.”

As there was so much foreign matter on the dies prior to the strikings of the Norweb and Lee 1802 dollars, it is unsurprising that some of it found its way into the recessed areas as well. There are numerous plausible scenarios involving sticky particles accidentally ending up on dies and it is unsurprising that matter fell into the recesses, and, in this case, on the portion of the die that struck Miss Liberty’s hair. Sticky particles could have fallen from gloves, shirts, or cloths used to wipe dies. There were no electric vacuum cleaners then in use at the Philadelphia Mint. There might also have been contaminants in materials or liquids used to polish dies, which tended to attract stuff.

On the Lee and Norweb 1802s,there small indentations in the hair that are very similar in shape to the indentations in the fields, the same kinds of particles. Like a series of dots may look look a line or a shape, a series of particles on a die, or just one piece of metal or fabric, may impress an indentation that looks like a scratch on a coin. Plus, some of the particles may have been wiry, sticklike, or rectangular in shape, as we imagine scratches and some kinds of contact marks to be.

Particles that fall into the recessed portions of the die, including the hair of Miss Liberty in this case, are ‘on the die’ rather than part of the die and lead to indentations on coins, which may be wrongly interpreted as scratches. If and when these particles are noticed and removed, such indentations will not appear on subsequent coins, if any, that were struck from the same pair of dies.

©2012 Greg Reynolds

Very informative column Greg, thanks a million! Certainly appreciate it!

You are correct in saying that the term “novodel” comes from the Russian. I can even break it down for you. It stems from the Russian words for “new (novy-novaya-novoye for the three genders, and ‘novo’ in the short form)” and “done/made (dyelat’ being the infinitive, dyelanno/zdyelanno as the participle).”

Therefore novodel (pronounced in Russian as “NAW-va-dyel,” and written as новодел) simply means “newly made,” or “newly done.”

Greg Reynolds article was very interesting but I have two points to make the Lee coin is the Norweb coin and the current Heritage offered coin. I agree the photos do not appear to match but close examination of all three coin in the pictures show a scratch on the Hair leading to the second highest curl on the right side of the hair next to the highest curl. None of the other specimens show this and I believe that it is a mark made to the coin not the die.

The other point I would like to make is that I also believe the coins were made earlier then the 1870’s I believe that the 1801 die may have been the first die attempted for the 1804 dollar but was rejected because of the punches used. I do not think we will ever find proof of when they were really made because the people who made them did not want to be discovered.

Extremely interesting column Greg. You are 100% correct about some surface features on coins being caused by foreign matter strike-throughs that become embedded in the die and appear on many different coins struck from that die. One need look no further than the 1801 and 1803 proof novodels for a convincing example of this phenomenon. All known examples of these issues show a linear depression on the reverse, from below NU in UNUM to the eagle’s wing, indicating that these issues were struck one right after the other. I think this happens more often on the anvil die, however, as gravity helps dislodge articles that become momentarily attached to the hammer die. You are also correct about the important role of toning in pedigree attributions.

That being said, I have to disagree with your theory about the Norweb and Lee 1802s being different coins. There would have to be A LOT of foreign objects sticking to the hammer die to recreate all those depressions on two different coins. There are also a few marks, like the one P. Scott Rubin mentions in Liberty’s hair, that are plainly contact marks, not planchet flaws or die anomalies. The coin was undoubtedly conserved at some point between its appearance in the Norweb sale and the Jack Lee catalog. Remember the magnificent toned 1893-S Morgan dollar in lot 3887 of the Norweb sale. It also became part of Jack Lee’s collection. When it reappeared in lot 7332 of the Chicago Signature and Platinum Night Auction (Heritage, 8/2011) everyone was surprised to note that it had been dipped. Either Jack Lee himself, or some unknown intermediary, seems to have had an unfortunate penchant for dipping high-grade coins. I believe the other differences you see in the photographs are due to light, shadow, and picture quality, which can cause the same coin to appear much different under different conditions. Best regards.

Below the main body of my article, please find an addendum, in which I respond to counterpoints put forth by David Stone and P. Scott Rubin. I thank both of them, Dwayne Z., and Marc Emory for commenting.

The last sentence should read If you are going to continue to believe that the Norweb and Lee coins are not the same, please let me know how you have marks only on these images and the images of all the other coins do not have these marks but others that the Lee and Norweb and other photos of this coin have.

Foreign matter on the fields of the dies was responsible for depressions and other indentations, and foreign matter on the ‘hair’ portion of the obverse die resulted in some small indentations as well, which can easily be wrongly interpreted as scratches.

I appreciate P. Scott Rubin’s second comment and I admit that I did not, in the original article, make it clear that foreign matter in the fields AND foreign matter on the devices results in indentations on coins WHEN THEY ARE MINTED. In such instances, there are fewer indentations on the design elements, partly because foreign matter is less likely to cling to the devices on the dies. I added a second addendum to my article, in which I explain this concept as best as I can at the present. This second addendum is published above. I hope that P. Scott Rubin and other coin enthusiasts will read it.

This article is very informative. Collectors today can not

truly appreciate the time ,research and resources that it takes

to write such an article or to write the well thought out

responses.Collectors every where should really be thankful!!

Besides the Breen book ,which is 35+ years old ,is there

a more up to date reference covering early proof and S.P.

strikings?