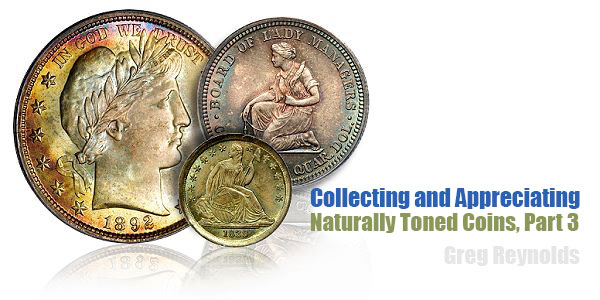

By Greg Reynolds for CoinWeek …..

In Part 1, I frame the topic and put forth the perspectives of very accomplished collectors regarding natural toning. As I discuss in Part 2, preferring coins with natural toning is a tradition at the core of coin collecting culture in the United States

Here in Part 3, I maintain that strongly favoring naturally toned coins goes beyond collector opinions and tradition. There have always been logical reasons for determining that coins with natural toning and/or mostly original surfaces are superior.

* * *

1.) Coin collecting has been a popular and serious pastime for around 150 years in the United States, and there has always been a strong tradition of valuing, all else being equal, coins with mostly original surfaces and/or natural toning over those that have been treated with acids (including dipping), artificially toned, surgically altered or otherwise deliberately affected by chemicals.

2.) The damage this causes to the layers of a coin’s surface is, to some extent, irreparable. The original state of the coin can never be restored, and will never fully return on its own. Parts of the coin are destroyed and, while some coins can largely recover, portions of the nature and history of such damaged coins are lost forever.

Please note that I am referring primarily to rare or at least scarce old coins. Usually, recently minted coins are minimally or not noticeably toned. So not much toning is destroyed when a modern coin is dipped in a standard acidic solution. For high-quality rare coins, dipping or ‘conservation’ almost always destroys toning.

Typically, a coin will be much brighter after it is dipped, and some will thus conclude that the coin’s luster is not impaired. Luster is the way that the metal flow lines on a coin reflect light. When layers are stripped via dipping, the characteristics of the flow lines are changed. The coin may end up being brighter than it was before, or even brighter than it was the moment it was minted, but destruction still occurred, however, and metal was removed.

Jeff Ambio very much agrees with statement number two. Ambio is the author of three recent books on coins and is a cataloguer for leading auction firms and coin dealers. He has analyzed and written about thousands of U.S. coins, including innumerable rarities.

“I believe that, if more collectors understood this point, it would really help to the put the coin doctors out of business,” he says.

Dipping changes the texture of a coin. Ambio and I agree that the toning that occurs after dipping–natural or not–will be different from the toning that would have occurred had the coin never been dipped.

There are subtle or sometimes blatant differences in the original finishes of coins. For example, Joe O’Connor mentions that some classic commemoratives were made with “matte textures”, while others were minted with “frosty finishes”. Still others are “semi-prooflike”.

I maintain that, in the 19th century, there were a substantial variety of differences in the finishes of coins, most of which are almost impossible to explain yet are important to examine. Dipping often takes much away from a coin.

Jeff Isaac has a different view.

“Coins with original surfaces that are dipped properly will not lose any discernible luster from the dipping bath,” he says. “I completely disagree that a coin that has been properly dipped has been damaged. Furthermore, there are different dipping solutions, some of which are more gentle than others that can remove the surface toning and residue without doing practical harm to the coin’s surface. It is wrong to condemn a dipped white coin. Toned coins, when dipped properly in the right solution, can look like they just came off the minting press. I like this look, as it brings me back in time, imparting a feeling of what it was like at the time the coin was made. Additionally, a bright untoned coin will not have hidden flaws that may exist under a toned coin’s surfaces. Beautiful toning may mask flaws.”

Isaac has been handling coins professionally since 1979, having begun collecting them in 1976. In the late 1980s and early ’90s, he was one of the nation’s leading wholesalers of rare coins and the successful bidder for some major rarities on the auction circuit. Additionally, Isaac was a grader at Professional Coin Grading Service (PCGS) for a short term and he was twice employed as a grader by Numismatic Guaranty Corporation (NGC) for a total of about four years. He is now an independent contractor for a major coin firm.

Rich Uhrich puts forth still another viewpoint:

Rich Uhrich puts forth still another viewpoint:

“Dipping only makes sense when the coin has some serious negative feature, and dipping to remove that feature might make the coin better, despite the fact that some metal is lost in the dipping process. A light dipping might improve a coin by removing some surface haze or other contaminant and the coin might actually look more attractive. A good example of this would be a Proof silver coin with haze that can be removed by dipping.”

Uhrich is a lifetime hobbyist, who has assembled collections of most all dates of U.S. copper, nickel and silver coins. In his free time, Uhrich once held a high-level position at a Fortune 500 firm, exercising an option for early retirement in 2006 to become a full-time coin dealer. His specialties are Bust and Liberty Seated silver coins.

Uhrich and Isaac both focus on the issue of removing unattractive matter on a coin through dipping. While Isaac is partial to the look of dipped coins, Uhrich points toward instances where a coin will look better after it is dipped solely because unattractive toning or contaminants will be removed. Isaac questions whether some in the hobby “have the right to impose” their tastes and preferences on others.

Though their perspectives on dipping are very different, Isaac and Uhrich both emphasize the aspect of eye appeal and, in my view, miss some logical points, of which aesthetics are only a part. A cultural rule that is favorable to dipping would not discourage dealers or collectors from dipping all their coins and would allow for multiple dips of each coin. It is crucial to consider the cumulative effects of changing the surfaces of the same coin on multiple occasions.

I (this writer) disagree. Suppose an item’s flaw or some other negative trait is noticeable only under high magnification. It is not logical to assume that such an aspect is not a serious problem. There are forgeries of coins that are so deceptive that they appear genuine to the naked eye, yet can be found to be forgeries with a microscope. Even though, in many cases, a microscope is needed to find the harm done by dipping a coin, it still makes sense to consider whether the harm done is substantial and/or has negative consequences for the future of the coin.

Not only is metal lost and toning destroyed, standard dipping and ‘conservation through surface-altering liquids’ (a common practice) change coins such that they become much more difficult to trace. In 2008, several leading experts told me that they did not recognize the Norweb 1893-S silver dollar–previously the finest known and very famous–after it was conserved. Some Eliasberg coins that have been dipped cannot now be traced back to the Eliasberg collection. Coins that are dipped or conserved often become unrecognizable.

3.) If dipping, artificial toning and surgical alterations were all considered desirable, then most rare coins would be modified to the extent that they would be unrecognizable. It is already tempting for some to market artificially colored or brightened coins. If such modifications were considered legitimate, then there would be no limit to the extent of artificial coloring and surgery to which coins would be subjected. The pedigrees and other historical information regarding the coins would tend to be lost; knowledge within the culture of coin collecting would be damaged or destroyed.

Jeff Ambio agrees such activities “cause pedigree markers to be lost or covered up. A coin’s association with great collections, such as Pittman or Eliasberg, may be forever hidden.”

Joe O’Connor addresses this point (#3) in relation to pre-1858 Proofs and high-grade pre-1840 business strikes. O’Connor emphasizes that coin experts “maintain rosters of the finest-known specimens with lists of prior ownership”.

“Dipping or artificially altering a coin that has such a strong historical record in an attempt to fool the next buyer will eventually be detected,” O’Connor says, “and that coin’s status will almost always decline in the condition-census roster, ultimately lowering its value.” O’Connor, a Chicago area dealer, is widely regarded as an expert in 18th- and 19th-century, high-quality U.S. coins and is particularly skilled in detecting original surfaces.

“Of course, it is important for coins to be traceable,” Uhrich says. “First, pedigrees are history. If all the coins were altered so none of them could be traced back to the great collections of the past, we in the coin collecting community would lose a lot. Second, pedigrees add value. A coin from the Eliasberg Collection deserves special note, and it also has additional value. Large cents from the Ted Naftzger Collection deserve special note, and have additional value. The great collectors throughout history had a lot of coins available to them, and these are the ones they chose to put in their collections.”

O’Connor focuses upon the importance of tracking “the pedigree chains and sales history for rare coins. Pedigrees establish a chain of ownership, continuity between collectors of different eras. Each collector can be part of something, part of the history of a coin. It is especially important to look back to know that a coin’s appearance has not changed over time.”

4.) The effects of much ‘coin doctoring’ occur days, weeks, months or even years after the respective coin is modified. It’s not unusual for blue or green paste to form and to spread in the fields of gold coins due to long-term chemical reactions stemming from past instances of ‘coin doctoring’. On coins of all metals, certain added colored substances will spawn additional colored substances and other residue.

Ambio declares that this (point #4) is “absolutely true”.

“[I’ve] seen many 19th-century silver coins in older PCGS and NGC holders where chemical reactions such as this have occurred. Particularly, there are plentiful examples of silver coins that have an unsightly haze that can be traced to dipping solutions.”

O’Connor agrees. “[Some] harmful effects of mechanically or chemically altering a coin’s surface may not be detected until some time after the coin is certified and encapsulated,” he says.

Jeff Isaac agrees that this point (#4) is “important”. He notes, however, that, “with the exception of coin doctoring that involves moving a coin’s metal, including polishing or otherwise smoothing surfaces, most coin doctoring is correctable. An unnatural process is more likely to be unstable because the process to create the affect was accelerated. I have seen many coins that were doctored that have changed over time. Often, some type of added film on the surface can turn or grow. It sometimes appears that the residue or film changes colors. These can look awful or they can just look different. Additionally, the residue from substances added by coin doctors can coagulate and get lumpy. Luckily, these coins can be brought back to an acceptable state by removing the residue. The metal composition of most non-copper coins can handle much more abuse than most people realize.”

Jeff Isaac agrees that this point (#4) is “important”. He notes, however, that, “with the exception of coin doctoring that involves moving a coin’s metal, including polishing or otherwise smoothing surfaces, most coin doctoring is correctable. An unnatural process is more likely to be unstable because the process to create the affect was accelerated. I have seen many coins that were doctored that have changed over time. Often, some type of added film on the surface can turn or grow. It sometimes appears that the residue or film changes colors. These can look awful or they can just look different. Additionally, the residue from substances added by coin doctors can coagulate and get lumpy. Luckily, these coins can be brought back to an acceptable state by removing the residue. The metal composition of most non-copper coins can handle much more abuse than most people realize.”

I find Isaac’s insights regarding the rehabilitation of coins that have been doctored to be surprising and fascinating. I hope that many of the rarities that have been mistreated will become fairly gradable in the future.

5.) If artificial toning and surgical additions are not strongly discouraged, then the very notion of quality will fade away. Dealers and collectors (or ‘hired artists’) will, instead of seeking naturally attractive coins, apply colors to and sculpt the surfaces of their coins. Does it make sense to regard rarities as a mold to play with and shape?

Ambio declares that this is a “huge point”. “If this process does not stop, there will eventually be few original coins left in any grade.”

Uhrich quips: “If such artificial means to improve a coin somehow become acceptable, we all might as well collect just colorized state quarters!”

O’Connor continues: “If all of the antique furniture were stripped and refinished to look ‘new’, there would be no reason to buy antique furniture.”

Joe points out that people then “could simply buy” reproductions.

“If all old rare coins were stripped and refinished, there would be no reason to buy genuine old coins,” he says. “People could just buy reproductions” of rare coins.

Unless coin doctoring is not strongly discouraged, “there will be no limit to the stripping and reworking of coins,” O’Connor warns.

I have seen the results of many variations of the “stripping and reworking” to which Joe refers. If artificial toning and surgical additions were openly permitted, then many rare coins would be changed to the point that they would be literally covered with additional substances: orange paste, blue and red chemicals that would not normally appear on coins, extra metal to fill in imperfections, putties and liquid plastics to fill in scratches or bring about artificial shines, added films and phony ‘Proof Cameo’-style white paint coatings.

One ‘coin doctor’ informed me that, when coppery areas on gold coins are removed with a torch, the resulting craters can be made to look like planchet defects. Regardless of whether additional modifications are effected, the torching of gold coins undoubtedly brings about artificial chemical reactions on the surfaces and forever changes coins. In my view, when acquiring pre-1934 U.S. gold coins, collectors should often choose ones that have coppery areas, which are typically termed ‘spots’.

O’Connor explains that “by doctoring a coin, someone is trying to create something that didn’t exist before. Collectors want the history and stories behind the coins. They do not want to collect newly altered coins. They want to collect the real thing.”

O’Connor explains that “by doctoring a coin, someone is trying to create something that didn’t exist before. Collectors want the history and stories behind the coins. They do not want to collect newly altered coins. They want to collect the real thing.”

Joe stresses that, when coins are doctored, “collectors lose an emotional attachment to them, and if coin doctoring is not controlled, the soul of the coin collecting community will be lost.”

Ambio, O’Connor, Isaac, Uhrich and myself all agree that, even though the two major grading services have graded many coins that should not have been graded, PCGS and NGC have performed valuable and very important services to the coin collecting community. Certainly, for pre-1934 coins valued at more than $500 each, and for many post-1934 issues, collectors should acquire coins that have been certified by PCGS or NGC.

Many pre-1934 U.S. coins that are not certified by PCGS or NGC are coins that the services refused to grade because of serious problems. Other scarce coins are overgraded by non-leading grading services. For coin collectors, buying PCGS- and NGC-certified coins involves much less risk than not doing so. Despite the imperfections of third-party grading services, it is clearly logical to buy PCGS- and NGC-certified coins. It is true, though, that some coins are not sufficiently valuable for certification fees to be worthwhile. It is important for all collectors to find experts who are willing to teach them about natural toning.

Conclusion

In sum, there are compelling cultural and logical reasons to highly value coins with natural toning and those that have been markedly dipped, artificially toned and/or surgically affected as having been harmed. Of course, the level of harm varies, and “all or nothing” thinking should be avoided.

It is very important not to underestimate the effectiveness of natural retoning.

Jeff Isaac notes that “many coins that have been enhanced artificially at one point in their life were then stored in accordance with the traditions of coin collectors and naturally retoned. Most such coins recovered to have predominantly natural surfaces.”

Unlike some experts who take a more rigid view and condemn coins that have ever been modified in any way, I (this writer) emphasize the superiority of natural toning and/or mostly original surfaces. Natural toning will often form on not-so-original surfaces. Plus, artificial toning on mostly original surfaces can sometimes be effectively removed and thus a mostly original coin without much natural toning may be very desirable.

For pre-1917 coins with much natural toning, it is frequently hard or even impossible to discern the extent to which each coin’s underlying surfaces are original. There are a large number of 19th-century coins that have naturally retoned after having been dipped or cleaned in the past, and I maintain that many of these truly grade from 65 to 67. It is not unusual for the positive aspects of natural retoning to outweigh the harm done by past dipping or cleaning. After all, cleaning may be light, moderate or heavy, and may pertain to all of or just small parts of a coin’s surfaces. It is common for natural toning to gradually cover areas that have been cleaned or contact-marked

A coin’s grade is the result of a calculation that includes positive and negative values. In my view, no pre-1934 coin should ever be graded ’70’ – and most awarded ’69’ grades are questionable. All such coins have some significant negative characteristics.

Usually, coins with a high degree of naturalness are superior to otherwise similar coins with a relatively low degree of naturalness. Moreover, it is logical to prefer circulated coins with natural toning and significantly original surfaces over uncirculated coins that appear moderately to heavily dipped, or that have been doctored. It is traditional, logical and imperative to strongly favor natural toning over artificial alternatives.

Consider the consequences of not doing so!

© 2017 Greg Reynolds (Reposted from an original article written for CoinLink)